The graph above shows data on normalized US hurricane losses 1900 to 2009 and was presented in a talk I gave today. Why is there no trend in the data? The two graphs below explain why. You can do the math.

There are no trends in normalized damage since 1900 because there are no trends in either hurricane landfall frequency (data from NOAA) or intensity (data from Chris Landsea through 2006) over that same period (but rather, a very slight decline in both cases). If our normalization were to show a trend then it would actually have some sort of bias in it. It does not, thus we can have confidence that the societal factors are well accounted for in the normalization methodology.

30 November 2010

Fabrications in Science

[UPDATE 12/6: Mickey Glantz has this to say on his Facebook page:

It is of course more than a little interesting that Science saw fit to ask one of my most vocal critics to review the book. Trenberth has been on the losing side of debates with me over hurricanes and disasters for many years. But even so, I am quite used to the hardball nature of climate politics, and that reviewer choice by Science goes with the territory. It says a lot about Science. Trenberth's rambling and unhinged review is also not unexpected. What is absolute unacceptable is that Trenberth makes a large number of factual mistakes in the piece, misrepresenting the book.

Science should publish a set of corrections. Here is a list of Trenberth's many factual errors:

1. TRENBERTH: "An example that he might have mentioned, but does not, is President George W. Bush's 2001 rejection of the Kyoto Protocol on the grounds that it would hurt the economy. "

kevin trenberth MAY know science but to ask him to review this interdisciplinary assessment is a joke played on readers by Science's editors. scientists are angry because they are losing control of the climate issues to other disciplines and NGOs. I think i will write a review of the climate models and i wonder if Science will print it!]You don't expect to pick up Science magazine and read an article that is chock full of fabrications and errors. Yet, that is exactly what you'll find in Kevin Trenberth's review of The Climate Fix, which appears in this week's issue.

It is of course more than a little interesting that Science saw fit to ask one of my most vocal critics to review the book. Trenberth has been on the losing side of debates with me over hurricanes and disasters for many years. But even so, I am quite used to the hardball nature of climate politics, and that reviewer choice by Science goes with the territory. It says a lot about Science. Trenberth's rambling and unhinged review is also not unexpected. What is absolute unacceptable is that Trenberth makes a large number of factual mistakes in the piece, misrepresenting the book.

Science should publish a set of corrections. Here is a list of Trenberth's many factual errors:

1. TRENBERTH: "An example that he might have mentioned, but does not, is President George W. Bush's 2001 rejection of the Kyoto Protocol on the grounds that it would hurt the economy. "

REALITY: Actually, Pielke discusses Bush's rejection of Kyoto on pp. 39 and 442. TRENBERTH: "Pielke treats economic and environmental gains as mutually exclusive"

REALITY: Not so. From p. 50, "[A]ction to achieve environmental goals will have to be fully compatible with the desire of people around the world to meet economic goals. There will be no other way."3. TRENBERTH: "Pielke does not address the international lobbying for economic advantage inherent in the policy negotiations. "

REALITY: Wrong again. The international economics of the climate debate are discussed on pp. 59, 65, 109, 219, 231, and 233 and are a theme throughout.4. TRENBERTH: "He objects to Working Group III's favoring of mitigation (which is, after all, its mission) while ignoring Working Group II (whose mission is adaptation)."

REALITY: Again, not so. Chapter 5 is about the balance between mitigation and adaptation in international policy and discusses both IPCC WG II and WG III (see pp. 153-155). What Pielke objects to is defining adaptation as the consequences of failed mitigation.5. TRENBERTH: "His claims that “the science of climate change becomes irrevocably politicized” because “[s]cience that suggested large climatic impacts on Russia was used to support arguments for Russia's participation in the [Kyoto] protocol”—as if there would be no such impacts and Russia would be a “winner”—look downright silly given the record-breaking drought, heat waves, and wildfires in Russia this past summer."

REALITY: Egregious misrepresentation. Trenberth selectively uses half of a quote to imply that Pielke was making a claim that he did not. The part left out by Trenberth (p. 156) was the counterpoint -- specifically that science that suggested few impacts on Russia was used in similar fashion by advocates to argue against the Kyoto Protocol. Pielke concludes, "In this manner, the science of climate change becomes irreovocably politiciized , as partisans on either side of the debate selectively array bits of science that best support their position."6. TRENBERTH: "Pielke stresses economic data and dismisses the importance of loss of life."

REALITY: Wrong again. Pielke discusses loss of life related to climate change on pp. 176-1787. TRENBERTH: "Geoengineering is also dealt with by Pielke, but only briefly."

REALITY Not so. Pielke devotes an entire chapter to geoengineering (Chapter 5).8. TRENBERTH: "[Pielke] does not address the practicality of storing all of the carbon dioxide."

REALITY: Again, wrong. Pielke addresses the practicality of carbon dioxide storage on pp. 133-134And even with all these errors and false claims, Trenberth concludes that the book is on the right track:

"[P]rogressively decarbonizing the economy and adopting an approach of building more resiliency to climate events would be good steps in the right direction"Anyone who has read The Climate Fix should also read Trenberth's review, as they will learn something about Science magazine and a part of climate science community. As is said, politics ain't beanbag, and climate politics are no different.

New Peer-Reviewed Paper on Global Normalized Disaster Losses

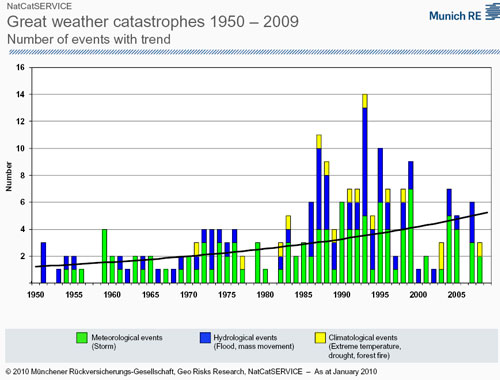

The LSE Grantham Institute, funded by Munich Re (whose global loss data is shown above), has published a new peer-reviewed paper on normalized global disaster losses.

Yet claims that global warming has led to increased disaster losses are a siren song to the media and advocates alike, with the most tenuous of claims hyped and the peer reviewed literature completely ignored. I don't expect that to change.

Eric Neumayer and Fabian Barthel, Normalizing economic loss from natural disasters: A global analysis, Global Environmental Change, In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 18 November 2010, ISSN 0959-3780, DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.10.004.The paper finds no evidence of upward trends in the normalized data. From the paper (emphasis added):

"Independently of the method used,we find no significant upward trend in normalized disaster loss.This holds true whether we include all disasters or take out the ones unlikely to be affected by a changing climate. It also holds true if we step away from a global analysis and look at specific regions or step away from pooling all disaster types and look at specific types of disasters instead or combine these two sets of dis-aggregated analysis. Much caution is required in correctly interpreting these findings. What the results tell us is that, based on historical data, there is no evidence so far that climate change has increased the normalized economic loss from natural disasters."This result would seem to be fairly robust by now.

Yet claims that global warming has led to increased disaster losses are a siren song to the media and advocates alike, with the most tenuous of claims hyped and the peer reviewed literature completely ignored. I don't expect that to change.

An Evaluation of the Targets and Timetables of Proposed Australian Emissions Reduction Policies

My paper on Australian emissions reduction proposals has now been published. Thanks to all those who provided comments on earlier versions. Here are the details:

Pielke, Jr., R. A. (2010), An evaluation of the targets and timetables of proposed Australian emissions reduction policies. Environmental Science & Policy , doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2010.10.008

This paper evaluates Australia’s proposed emissions reduction policies in terms of the implied rates of decarbonization of the Australian economy for a range of proposed emissions reduction targets.The paper uses the Kaya Identity to structure the evaluation, employing both a bottom-up approach (based on projections of future Australian population, economic growth,and technology) as well as a top-down approach (deriving implied rates of decarbonization consistent with the targets and various rates of economic growth). Both approaches indicate that the Australian economy would have to achieve annual rates of decarbonization of 3.8–5.9% to meet a 2020 target of reducing emissions by 5%,15% or 25% below 2000 levels, and about 5% to meet a 2050 target of a 60% reduction below 2000 levels. The paper argues that proposed Australian carbon policy proposals present emission reduction targets that will be all but impossible to meet without creative approaches to accounting as they would require a level of effort equivalent to the deployment of dozens of new nuclear power plants or thousands of new solar thermal plants within the next decade.

29 November 2010

Africa is Big

The Economist provides the maps above and a discussion of their origin from one Kai Krause, a graphics expert who is engaged in a battle against "immappancy." It is a worthy battle. In a standard Mercator projection, Africa is indeed deemphasized. Even maps have politics.

Aynsley Kellow's Science and Public Policy Deeply Discounted

Aynsley Kellow has written to notify me that his excellent book, Science and Public Policy: The Virtuous Corruption of Virtual Environmental Science (2007, Edward Elgar), is on sale for $40, which is a full $70 off of its list price.

Here is a blurb from the book's website:

Here is a blurb from the book's website:

‘Crusading environmentalists won’t like this book. Nor will George W. Bush. Its potential market lies between these extremes. It explores the hijacking of science by people grinding axes on behalf of noble causes. “Noble cause corruption” is a term invented by the police to justify fitting up people they “know” to be guilty, but for whom they can’t muster forensic evidence that would satisfy a jury. Kellow demonstrates convincingly, and entertainingly, that this form of corruption can be found at the centre of most environmental debates. Highly recommended reading for everyone who doesn’t already know who is guilty.’

– John Adams, University College London, UK

Science and Public Policy

by Aynsley Kellow

Web link: http://www.e-elgar.com/Bookentry_Main.lasso?id=12839

Normally £59.95/$110.00 Special price $40/£25 + postage and packing

To order this book please email (with full credit card details and address):

sales@e-elgar.co.uk, or on our website enter 'Kellowoffer' in the special

discount code box after entering your credit card details and the discount

will be taken off when the order is processed.

Contents:

Preface

1. The Political Ecology of Pseudonovibos Spiralis and the Virtuous Corruption of Virtual Science

2. The Political Ecology of Conservation Biology

3. Climate Science as ‘Post-normal’ Science

4. Defending the Litany: The Attack on The Skeptical Environmentalist

5. Sound Science and Political Science

6. Science and its Social and Political Context

Bibliography

Index

Quantitative Methods of Policy Analysis

In the upcoming Spring, 2011 term, I am teaching a graduate seminar titled "Quantitative Methods of Policy Analysis." Here is a short course description:

ENVS 5120The course text will be Analyzing Public Policy: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques, 2nd Edition (2010), by Dipak K. Gupta. The figure at the top of this post will be discussed on the first day of class. There are seats available in the course, so if you are a CU student and interested in enrolling, please contact me.

Quantitative Methods of Policy Analysis

This course will survey a range of quantitative methodologies commonly used in applied policy analysis. The course will cover the role of the analyst and analyses in policy making, formal models of the policy process, the role of quantification in problem definition, basic statistics and probability, data and its meaning (including uncertainties), projection and prediction, decision analysis and game theory, government budgeting, cost-benefit analysis, and graphical methods. The course will be organized around a textbook, individual semester-long projects and various problem sets. No prerequisites are necessary.

23 November 2010

Some Changes in the Works

Now that my fall "book tour" is just about over and The Climate Fix is well launched, it is time to consider what is next. As readers of this blog will well know, for the past several years I have focused intensively on the climate issue with near daily postings on various aspects of the issue. For me, the resulting interactions on and off blog have been extremely illuminating and rewarding. But just as after The Honest Broker was published, a book's publishing signifies that it is time for an academic change of course.

For the next several years the focus of my work is not going to be on climate issues, but rather, issues associated with innovation and technology, with energy only a small part of that focus. My next book is already underway and I have decided to spend most of my time in 2011 on it and other topics that I've neglected, meaning that something else will have to give. That something else will be the intensive focus on the climate debate and the daily climate blogging associated with it. If I believe my own analysis -- and I think I do -- then the broad outlines of that debate are unlikely to change anytime soon. I'll continue to be a strong and active advocate for energy innovation and adaptation.

I have no doubts that there will be continued occasion on this blog to discuss and debate the issues raised in The Climate Fix, and there will be things worth discussing related to climate. So in the future I will restrict my discussions of climate to Tuesdays. What appears on this blog on the other days could be something related to my new book, some random musings, high-quality football analysis or nothing at all. We'll see.

The entire crack staff here at this blog has been given some well-deserved time off, so posting will be scarce in the coming days and weeks as the holidays are here. Comments will still be cleared, but please have patience if it is slow.

Thanks again to all the readers and commenters! Happy Holidays!

For the next several years the focus of my work is not going to be on climate issues, but rather, issues associated with innovation and technology, with energy only a small part of that focus. My next book is already underway and I have decided to spend most of my time in 2011 on it and other topics that I've neglected, meaning that something else will have to give. That something else will be the intensive focus on the climate debate and the daily climate blogging associated with it. If I believe my own analysis -- and I think I do -- then the broad outlines of that debate are unlikely to change anytime soon. I'll continue to be a strong and active advocate for energy innovation and adaptation.

I have no doubts that there will be continued occasion on this blog to discuss and debate the issues raised in The Climate Fix, and there will be things worth discussing related to climate. So in the future I will restrict my discussions of climate to Tuesdays. What appears on this blog on the other days could be something related to my new book, some random musings, high-quality football analysis or nothing at all. We'll see.

The entire crack staff here at this blog has been given some well-deserved time off, so posting will be scarce in the coming days and weeks as the holidays are here. Comments will still be cleared, but please have patience if it is slow.

Thanks again to all the readers and commenters! Happy Holidays!

22 November 2010

Colorado Rapids Win MLS Cup!

It was not the most exciting match, though the added extra time was intense. The referee was mostly out to lunch throughout the game and the game MVP, Colorado's Conor Casey had his name butchered in the presentation of the trophy. Colorado was even the 7th seed. Such is to be expected I suppose in a young league still making its way.

But so what? They are our team and this is their first trophy, and that is worth celebrating! Highlights below.

But so what? They are our team and this is their first trophy, and that is worth celebrating! Highlights below.

Groupthink or . . . Beware of Climate Labels

Over the weekend I was on an email list of prominent environmental journalists, bloggers, academics and activists in which one blogger raised the question of what terminology to use to describe those folks, you know, the skeptics or deniers. I watched in disbelief as people that I respect entertained the question in all seriousness. A climate scientist helpfully made the political connection explicit by recommending the term "inactivists." Several of the people on the list had in the past used such terms to try to delegitimize my work.

I about blew a seam. Seriously. I emailed the list explaining that this exercise was insane, and about as useful as debating what to call people with dark colored skin -- I can think of a lot of terms used for that purpose. But why go there? The answer? Because there is an US and a THEM, and being able to tell the difference is important if we are to put people into bins and delegitimize them.

Of course on the email list there was no consensus as to who the US is and who the THEY is, but they did agree that WE needed terms for THEM.

It would have been totally depressing except for the fact that one journalist spoke up to show some uncommon common sense, suggesting that describing context might be more useful than stripping it away. Some folks did not engage, so perhaps there is additional hope. Our ability to have healthy discussions on climate change remains quite challenging.

I've asked to be taken off the list, as I am clearly not one of them. Put me in the category of people who think that trying to divide the world according to views on some aspects of climate science is just a bad idea. It is especially a bad idea for journalists and policy wonks.

You can participate in the farce by entering your vote in the poll above.

I about blew a seam. Seriously. I emailed the list explaining that this exercise was insane, and about as useful as debating what to call people with dark colored skin -- I can think of a lot of terms used for that purpose. But why go there? The answer? Because there is an US and a THEM, and being able to tell the difference is important if we are to put people into bins and delegitimize them.

Of course on the email list there was no consensus as to who the US is and who the THEY is, but they did agree that WE needed terms for THEM.

It would have been totally depressing except for the fact that one journalist spoke up to show some uncommon common sense, suggesting that describing context might be more useful than stripping it away. Some folks did not engage, so perhaps there is additional hope. Our ability to have healthy discussions on climate change remains quite challenging.

I've asked to be taken off the list, as I am clearly not one of them. Put me in the category of people who think that trying to divide the world according to views on some aspects of climate science is just a bad idea. It is especially a bad idea for journalists and policy wonks.

You can participate in the farce by entering your vote in the poll above.

21 November 2010

Emissions Elasticity Test Results are In

In March, 2009 I noted that the projected decline in carbon dioxide emissions provided a chance for a serendipitous policy experiment:

Because there is a long history of assuming rates of decline in energy intensity and carbon intensity that are simply not matched by what is happening in the real world. As the AFP explains:

The results of the serendipitous emissions elasticity experiment provides additional, empirical confirmation of the merits of our arguments. Additional analysis can be found here for the world (graph at the top of this post) and here for the US (graph below), with trends in both instances going the wrong way.

When we eventually learn what happens to global emissions in response to the economic downturn, we will learn something new about the relationship of GDP growth and emissions. In recent years that relationship has strengthened. What will 2009 tell us?A paper published in Nature Geoscience today provides the results of that experiment. The BBC reports:

Why were they expecting much more?Carbon emissions fell in 2009 due to the recession - but not by as much as predicted, suggesting the fast upward trend will soon be resumed.Those are the key findings from an analysis of 2009 emissions data issued in the journal Nature Geoscience a week before the UN climate summit opens.

Industrialised nations saw big falls in emissions - but major developing countries saw a continued rise.

The report suggests emissions will begin rising by 3% per year again.

"What we find is a drop in emissions from fossil fuels in 2009 of 1.3%, which is not dramatic," said lead researcher Pierre Friedlingstein from the UK's University of Exeter.

"Based on GDP projections last year, we were expecting much more."

Because there is a long history of assuming rates of decline in energy intensity and carbon intensity that are simply not matched by what is happening in the real world. As the AFP explains:

The global decrease was less than half that had been expected, because emerging giant economies were unaffected by the downturn that hit many large industrialised nations.The overly optimistic assumptions of energy and carbon intensity decline was at the core of our 2008 paper in Nature, titled Dangerous Assumptions, which can be found here in PDF.

In addition, they burned more coal, the biggest source of fossil-fuel carbon, while their economies struggled with a higher "carbon intensity," a measure of fuel-efficiency.

The results of the serendipitous emissions elasticity experiment provides additional, empirical confirmation of the merits of our arguments. Additional analysis can be found here for the world (graph at the top of this post) and here for the US (graph below), with trends in both instances going the wrong way.

Plenty of Energy

Last week's New York Times had an article arguing that there are plenty of fossil fuels available to meet projected demand for coming decades. If that is the case, then all the more reason for accelerated efforts to increase that demand by expanding access and to put a small price on today's energy supply, while it is plentiful and relatively cheap, in order raise the funds necessary to invest in innovation to build a bridge to tomorrow.

Here is an excerpt:

The entire NY Times article is worth a read.

Here is an excerpt:

Energy experts now predict decades of residential and commercial power at reasonable prices. Simply put, the world of energy has once again been turned upside down.For those interested in stemming the accumulating carbon dioxide in the atmonsphere, even adopting agressive policies in that direction won't change the underlying dynamics:

“Oil and gas will continue to be pillars for global energy supply for decades to come,” said James Burkhard, a managing director of IHS CERA, an energy consulting firm. “The competitiveness of oil and gas and the scale at which they are produced mean that there are no readily available substitutes in either one year or 20 years.”

Some unpleasant though predictable consequences are likely, of course, as the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico this spring demonstrated. Some environmentalists say that gas from shale depends on drilling techniques and chemicals that may jeopardize groundwater supplies, and that a growing dependence on Canadian oil sands is more dangerous for the climate than most conventional oils because mining and processing of the sands require so much energy and a loss of forests.

And while moderately priced oil and gas bring economic relief, they also make renewable sources of energy like wind and solar relatively expensive and less attractive to investors unless governments impose a price on carbon emissions.

“When wind guys talk to each other,” said Michael Skelly, president of Clean Line Energy Partners, a developer of transmission lines for renewable energy, “they say, ‘Damn, what are we going to do about the price of natural gas?’ ”

Oil and gas executives say they provide a necessary energy bridge; that because both oil and gas have a fraction of the carbon-burning intensity of coal, it makes sense to use them until wind, solar, geothermal and the rest become commercially viable.

“We should celebrate the fact that we have enough oil and gas to carry us forward until a new energy technology can take their place,” said Robert N. Ryan Jr., Chevron’s vice president for global exploration.

Mr. Skelly and other renewable energy entrepreneurs counter that without a government policy fixing a price on carbon emissions through a tax or cap and trade, the hydrocarbon bridge could go on and on without end.

Even in an alternative world where there is a concerted, coordinated effort to reduce future carbon emissions sharply, the International Energy Agency projected oil demand would peak at 88 million barrels a day around 2020, then decline to 81 million barrels a day in 2035 — just fractionally less than today’s consumption.It is not necessary to agree with rosy scenarios of energy abundance to recognize that the current approach to dramatically reducing carbon dioxide emissions is not going to work, even if successful on its own terms. The sooner we start building that bridge to the future the sooner we can walk across it. It won't be built by targets and timetables for emissions reductions, nor by putting a price on carbon.

Natural gas use, meanwhile, would increase by 15 percent from current levels by 2035. In contrast, global coal use would dip a bit, while nuclear power and renewable forms of energy would grow considerably.

No matter what finally plays out, energy experts expect there will be plenty, perhaps even an abundance, of oil and gas. IHS CERA, which monitors oil and gas fields around the world, projects that productive capacity for liquid fuels could rise to 112 million barrels a day in 2030 (including 2.75 million barrels in biofuels), from 92.6 million barrels a day this year.

“The estimates for how much oil there is in the world continue to increase,” said William M. Colton, Exxon Mobil’s vice president for corporate strategic planning. “There’s enough oil to supply the world’s needs as far as anyone can see.”

More promising still is that the growing oil production comes from a variety of sources — making the world less vulnerable to a price war with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries or an outbreak of violence in a major producing country like Nigeria. As IHS CERA and other oil analysts see it, new oil is going to come from both conventional and unconventional sources — from anticipated expansions of fields in Iraq and Saudi Arabia and from a continued expansion of deepwater drilling off Africa and Brazil, in the Gulf of Mexico and across the Arctic, where hopes are high in the oil world, although little exploration has yet been done.

The vast oil sands fields in western Canada, deemed uneconomical by many oil companies as few as 15 years ago, are now as important to global supply growth as the continuing expansions of fields in Saudi Arabia, the current No. 1 producer.

“We’ve got a wealth of opportunities to address around the world,” said Mr. Ryan, Chevron’s vice president.

“We have quite a few deepwater settings all over the world, some of them very new, like the Black Sea. There are Arctic settings. We have efforts under way re-exploring Nigeria, Angola, Australia. The easy stuff has been found, that’s true, but in the end, we still have many basins in the world to explore or to re-explore.”

The entire NY Times article is worth a read.

18 November 2010

Brilliant Speech by Aggreko CEO Rupert Soames

Here is a speech that everyone interested in climate and energy policy should watch. Speaking before the Scottish parliament earlier this week, Rupert Soames, CEO of Aggreko -- a world leader in temporary energy supply -- delivers some straight talk to policy makers (BBC coverage). He focuses on Great Britain, but the lessons are of broad relevance. Have a look.

17 November 2010

About that 2020 UK Climate Change Act Emissions Reduction Target

At tonite's vibrant discussion of climate science, policy and the media at the British Council, I commented that the UK Climate Change Act was doomed to failure in meeting its 34% target for emissions reductions below a 1990 baseline by 2020. In the discussion with the audience, a familiar voice boomed from the back of the room that most climate experts would disagree with my assessment.

Today the UK National Grid provided some additional insight on this issue when it issued a press release on expected renewable energy by 2020:

Using the simple math of energy and decarbonization from The Climate Fix, 9 GW works out to the equivalent amount of carbon-free energy as produced by 12 nuclear power plants. In The Climate Fix, I argue that the UK needs 40 nuclear power plants worth of carbon free energy by 2015 (at the latest) to be on track to meeting its emissions reduction goal for 2020. (See also this paper.) So the UK is 5 years and at least 28 nuclear power plants worth of carbon free energy short (to get from 2015 to 2020 it would need dozens more). So I'll stand by my judgment.

If that voice from the back of the room wishes to contest these numbers, he is welcome to do so here, but somehow I doubt he will;-)

Today the UK National Grid provided some additional insight on this issue when it issued a press release on expected renewable energy by 2020:

A new report published by National Grid today shows that 31,950 MW of existing and proposed renewable generation have agreements in place to connect to the high voltage transmission system by 2020, placing the UK on track to meet 2020 renewable targets.So 27 GW of new capacity from renewables works out to 9 GW of supply at a 33% efficiency (and the word on the London street, literally, is that 33% is overly generous).

National Grid analysis identifies that about 29,000 MW of renewable transmission connected generation capacity is needed to meet the UK government’s target of 15 per cent of energy to come from renewable sources by 2020.

National Grid’s Transmission Networks Quarterly Connections Update, published today, shows:

Current transmission connected renewable generation: 4,950 MW

Proposed renewables projects with connection agreements up to 2020 as at 26 October 2010: 27,000 MW

Using the simple math of energy and decarbonization from The Climate Fix, 9 GW works out to the equivalent amount of carbon-free energy as produced by 12 nuclear power plants. In The Climate Fix, I argue that the UK needs 40 nuclear power plants worth of carbon free energy by 2015 (at the latest) to be on track to meeting its emissions reduction goal for 2020. (See also this paper.) So the UK is 5 years and at least 28 nuclear power plants worth of carbon free energy short (to get from 2015 to 2020 it would need dozens more). So I'll stand by my judgment.

If that voice from the back of the room wishes to contest these numbers, he is welcome to do so here, but somehow I doubt he will;-)

RMS Responds to the Sarasota Herald-Tribune

Several colleagues shared this letter submitted by RMS to the Sarasota Herald-Tribune's recent articles about reinsurance and catastrophe models. I offer several comments below the letter.

First, Shah is correct that the RMS outlook does not offer deterministic predictions. However, the measured language in the letter to the editor is contrary to how RMS characterized its outlook at the time. Consider this excerpt from a peer-reviewed paper describing its prediction methodology published subsequent to its issuance of its 2006-2010 prediction (PDF):

Second, Shah states:

Along with its peers, RMS is an important company. They do work that potentially helps make the global reinsurance and insurance industry do its work with a closer connection to empirical science. It is precisely because RMS is so important that it merits close attention. Like ratings agencies, RMS and other catastrophe modelers are too important to a range of public outcomes to be left to govern themselves. As much as cat modelers may not welcome greater external attention and accountability, as a result of their success and importance, that time has come.

Letter to the EditorI have two responses to this letter.

Your article ‘Florida Insurers Rely on Dubious Storm Model’ (November 14) contains some key inaccuracies about why and how RMS derived its medium-term hurricane risk model, and how these models are used by insurers.

Most fundamentally, catastrophe models deliver probabilistic forecasts not deterministic predictions. A probabilistic activity forecast means that, on average, a certain number of hurricanes can be expected over a period of time. The actual number experienced in a particular period will be just one sample from a broad distribution of possible outcomes.

There is widespread agreement within the scientific community that the number of intense North Atlantic hurricanes has increased since the 1970s, and that since 1995 overall hurricane frequency has been significantly higher than the long-term historical average since 1900. The question is, how much higher is the frequency and how will it impact hurricanes making landfall in the U.S.?

Given the lack of scientific consensus on this subject, we have attempted to answer this question by gaining the perspective of expert hurricane climatologists. The scientists were deliberately kept at a distance from the commercial implications of their recommendations. In our annual reviews of medium-term activity rates (the next five years), we have worked with a total of 17 leading experts, representing a broad spectrum of opinions. The process has evolved year on year, including the introduction of an independent moderator to oversee the elicitation in 2007. More recently we have employed a range of forecast models and methodologies subject to peer review in a scientific publication. Even when the experts involved and the scientific forecasting models have changed, the results of the five-year forecasts have remained remarkably consistent.

If RMS had been estimating medium-term activity rates during the 1970s and 1980s, the medium-term view would have shown lower activity than the historical average of activity. It should also be noted that 2010 has been another very active year for North Atlantic hurricanes. Fortunately none of these made landfall in Florida.

As an independent catastrophe risk modeler, the aim of our models has always been to provide the best unbiased estimate of risk to help the insurance industry and policy-holders to recognize and manage, and where possible, reduce the risk through the application of risk mitigation programs and initiatives. There is no commercial advantage for us to overstate the risk.

Pricing insurance risk involves a complex set of decisions. Models help determine the key drivers of risk, allowing insurers and reinsurers to understand their exposure to catastrophic loss. Other market conditions, such as the worldwide shortage of capital after the high-loss years of 2004 and 2005, also have dramatic influences on the availability and pricing of insurance.

We welcome review and debate of the timeframe over which catastrophe models should be used to characterize hurricane risk.

However, this debate should be based on a balanced and constructive view of the facts.

Sincerely,

Hemant Shah

President & CEO

Risk Management Solutions (RMS)

First, Shah is correct that the RMS outlook does not offer deterministic predictions. However, the measured language in the letter to the editor is contrary to how RMS characterized its outlook at the time. Consider this excerpt from a peer-reviewed paper describing its prediction methodology published subsequent to its issuance of its 2006-2010 prediction (PDF):

The medium-term perspective is more specifically defined here as a window covering the next 5 yr. There are both scientific and business reasons for choosing the 5-yr horizon. The variance of predictions over 5 yr is smaller than that of seasonal forecasts, in part because of the way that the variations accompanying the state of the El Ni˜no are implicitly accounted for, as 5 yr nears the average period of one ENSO cycle. Predictions at longer timescales, such as 10 or 20 yr are also found to be less skillful, given the observed multidecadal variability. Five yr also bound most business applications within the insurance industry, whether it is planning for capital allocation or for transferring financial risk through Catastrophe Bonds, for example.There is no discussion of uncertainties or probabilities associated with the prediction in the paper, and the term "prediction" is used throughout.

Second, Shah states:

Even when the experts involved and the scientific forecasting models have changed, the results of the five-year forecasts have remained remarkably consistent.This is indeed remarkable. So remarkable that after participating as an RMS elicitator in 2008 I looked into it and found that the results have little to do with choice of experts, but rather, the methodology employed by RMS. Of course the results changed little. When RMS did change its methodology a bit, the expected losses dropped a bit, and RMS suspended its elicitation process.

Along with its peers, RMS is an important company. They do work that potentially helps make the global reinsurance and insurance industry do its work with a closer connection to empirical science. It is precisely because RMS is so important that it merits close attention. Like ratings agencies, RMS and other catastrophe modelers are too important to a range of public outcomes to be left to govern themselves. As much as cat modelers may not welcome greater external attention and accountability, as a result of their success and importance, that time has come.

Report from The Legatum Debate

[UPDATE: Benny Peiser sends the following note with a request for it to be posted:

RogerI'll certainly post up the video when available!]

Thanks for inviting a response to your colourful story. I would prefer to refrain from any comment until the video of the debate is up so that interested readers can compare the actual arguments of our discussion with your recollection of it. It would be nice if you could post this note.

Thanks

Benny

Last night in Mayfair, I engaged Benny Peiser, of the Global Warming Policy Foundation, and Dalibor Rohac, of the Legatum Institute in a debate over the role of government in energy innovation. The event was well attended and the Legatum Institute provided a first rate forum for discussion and a wonderful reception afterward.

In the debate I opened by making several points. One is that debates over whether governments should be involved in innovation policy miss the point -- the fact is that governments are deeply engaged in innovation policies already. The issue is thus how should governments be involved in innovation policies.

I then characterized and briefly six reasons why public investments in energy innovation makes sense:

- Containing energy costs

- Securing energy security

- Expanding energy access

- Ending damaging energy subsidies

- Reducing carbon dioxide emissions

- Addressing other environmental consequences

In response, Benny Peiser expressed some dismay that I didn't choose to focus my remarks on climate. He seems to have missed the discussion in my book about obliquity and "policy jujitsu"! His view is quite simple and principled -- government action should be minimized as much as possible. Period. He believes that everything government touches leads to waste or failure, and extends this view to the energy sector. Benny explained that nations around the world, and indeed the world as a whole, do not in fact have any sort of energy problem, as fuels are cheap and the free market is doing its job meeting demand. He reveled in citing a litany of failures of government policy, particularly as related to climate in recent years.

Dalibor Rohac joined in with some scathing criticism of my book, arguing that it failed to rise even to the standards of conventional economists who argue that climate change represents a problem of unpriced externalities. Like Peiser, Rohac expressed disdain that governments would have any role whatsoever (in anything, as far as I could tell).

Part of the disagreement is clearly ideological -- Peiser and Rohac presented standard libertarian views on the role of government. At some level, such arguments are unresolvable, as they are grounded in different worldviews and orientations. Giving them a good airing is sometimes worthwhile. While Rohac never really went beyond theoretical, on points that can be adjudicated empirically raised by Peiser, I think that he is simply wrong on a number of points according to the evidence.

While he may not think that there is an energy problem, he is very much isolated in that view, as judged by the actions of governments and businesses around the world, with respect to the six points that I raise above. And irrespective of Peiser's and Rohac's views on the proper role of government, the realpolitik is that governments are and will continue to be deeply involved in innovation policies, and there are many examples of such policies contributing to public aims. I explained in the discussion that I have no desire to debate issues of climate science with Benny, and in fact I would grant in the debate (but not agree with) every one of his points on climate science, as they are related to only one of the 6 justifications that I offered for action on energy innovation. Ultimately, you can't beat something with nothing, and ideology doesn't expand energy access, keep the lights on and sustain reasonable fuel prices.

The early evening ended with the debate spilling over to the reception, where I met many new and interesting people. I left the event agreeing to disagree with Benny and Dalibor, and promising to re-engage the debate in the future. My mind was not changed, and I doubt theirs was either, but the event was worthwhile because I learned more about their views and those of the GWPF and the Legatum Institute, and hopefully they learned something more about my views.

Note: If Benny or Dalibor wish to add their reflections I am happy to add those here.

Lecture at LSE on Friday

Fixing Climate Policy

LSE Mackinder Programme for the Study of Long Wave Events public lecture

Date: Friday 19 November 2010

Time: 5-7pm

Venue: Sheikh Zayed Theatre, New Academic Building

Speaker: Professor Roger Pielke Jr

Chair: Professor Gwyn Prins

The diplomatic disaster that was the Copenhagen climate conference in December 2009 signalled to many that climate policy needed to change course. In this talk, Professor Roger Pielke Jr. of the University of Colorado will explain why the proposed policies that have been at the centre of the climate debate for decades are doomed to failure, and what an alternative way forward might look like.

Roger A. Pielke Jr is Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado and a Fellow of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences where he served as the Director of the Center for Science and Technology Policy Research from 2001-2007. Roger's research focuses on the intersection of science and technology and decision making. Formerly a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, he is the author of several books including the recently-published The Climate Fix: What Scientists and Politicians Won't Tell You About Global Warming. He is currently Visiting Senior Fellow, Mackinder Programme, LSE.

This event is free and open to all with no ticket required. Entry is on a first come, first served basis. For any queries email Gwyn Prins g.prins@lse.ac.uk|.

If you are planning to attend this event and would like details on how to get here and what time to arrive, please refer to Coming to an event at LSE

16 November 2010

Colorado Rapids in MLS Championship Game

In our little corner of the soccer world, Colorado Rapids are in the MLS championship game on Sunday, against some other team. Need I say that Colorado is an international partner with Arsenal, sharing an owner? Probably not, as the future has been foretold ;-) Enjoy Sunday! I sure will . . . .

15 November 2010

Baseball Deniers

Is it possible that some non-zero proportion of Americans believe something that is widely accepted as not true? Surely, in this day and age, that cannot be the case.

Witness, however, Bud Selig, Commissioner of Major League Baseball, cited in the New York Times:

Witness, however, Bud Selig, Commissioner of Major League Baseball, cited in the New York Times:

The old chestnut about Abner Doubleday’s inventing baseball in a cow pasture in upstate New York has been so thoroughly debunked that it has taken a position in the pantheon of great American myths, alongside George Washington’s cherry tree, Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed.The enduring myth of Abner Doubleday has prompted many calls for better baseball education and a call for sports reporters to end the "balance as bias" reporting in which those deniers such as Selig are given a forum to propagate their long debunked views. Again, the NYT:

So it came as a surprise when a letter surfaced recently on the Internet in which the commissioner of Major League Baseball, Bud Selig, wrote an author who inquired of his views on baseball history: “From all of the historians which I have spoken with, I really believe that Abner Doubleday is the ‘Father of Baseball.’ I know there are some historians who would dispute this, though.”

The letter touched off ridicule from historians and bloggers and provided fresh legs to an enduring legend that was discredited almost from the moment it was fashioned — in 1908, after the overlords of baseball sought an American creation story for the game and settled on a dead Civil War hero.

[F]or decades there has been virtually no debate among credible historians about whether Doubleday had any role in the founding of baseball, which most agree evolved incrementally from earlier games of bats and balls in England.With the prevalence of baseball deniers at the highest echelons of baseball governance, it is no wonder that we have seen steroids scandals and the elevation of the San Francisco Giants, among other tragedies. For better baseball decision making it is time for a renewed campaign to defeat the deniers. Abner Doubleday, here we come.

“The thing that amazes me is the durability of this idea,” said Lawrence McCray, a political scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the chairman of the origins committee at the Society of American Baseball Research. “You just don’t run into people now who think of this as historically accurate.”

The circumstances of the mythmaking have long been embraced as a quirky and colorful chapter of the game’s past. Even the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., the town where Doubleday supposedly invented the game in 1839, treats the story as fiction.

“The Doubleday Myth Is Cooperstown’s Gain” is the headline of an article in a book published this year by the Hall of Fame. “The Doubleday Myth has since been exposed,” Craig Muder, a Hall of Fame official, wrote in the book. “Doubleday was at West Point in 1839, yet ‘The Myth’ has grown so strong that the facts will never deter the spirit of Cooperstown.”

In fact, according to the baseball historian John Thorn, the only documented connection between Doubleday and baseball is a letter he wrote in 1871, while commanding a regiment of African-American soldiers in Texas, asking his superiors to “purchase baseball implements for the amusement of the men.”

Most historians contend that baseball directly evolved from English games like rounders and cricket and that it has even earlier roots in bat and ball games stretching as far back as 2500 B.C. in Egypt, where the pharaohs played a game called seker-hemat.

Instead of denoting one founder of baseball, the historiography has coalesced around a collection of men who advanced the game toward its modern version. Among the most prominent are Alexander Cartwright, credited with developing many rules of the modern game in New York City in the 1840s and with helping to form the New York Knickerbockers, and Henry Chadwick, a pioneering journalist in scorekeeping and statistics. Others, Thorn said, include Daniel Lucius Adams, a Knickerbockers player credited with establishing 90 feet as the distance between bases, and Louis Fenn Wadsworth, credited by some for setting the standards of nine players and nine innings.

“One of the things that distinguishes baseball from football and basketball is there is no clear inventor of the game,” said Andrew Schiff, who wrote “The Father of Baseball,” a biography of Chadwick. “Chadwick is called ‘the Father of Baseball’ not because he invented it but because he nurtured the game as it developed.”

Thorn is finishing a book about baseball’s origins titled, “Baseball in the Garden of Eden: A Secret History of the Early Game,” scheduled for publication in March. He said Selig’s apparent beliefs were testament to the power of myths in American culture and the connection between baseball and youthful innocence.

“The real question is, why do we hold on to myths?” Thorn said. “Some of the best parts of us as adults are these very things that have survived from childhood, including our idealism.”

He added: “It’s merely odd that the commissioner believes this. It is surprising. I don’t think you can mistrust his other judgments.”

14 November 2010

The $82 Billion Prediction

The Sarasota Herald-Tribune has an revealing article today about the creation in 2006 of a "short-term" hurricane risk prediction from a company called Risk Management Solutions. The Herald-Tribune reports that the prediction was worth $82 billion to the reinsurance industry. It was created in just 4 hours by 4 hurricane experts, none of whom apparently informed of the purposes to which their expertise was to be put. From the article:

RMS earlier this year admitted that the inclusion of that graph was a mistake, as it could have been "misleading."

And, you might ask, how did that five-year "short term" prediction from RMS made for 2006-2010 actually pan out? As you can see below, not so good.

Here is the agenda for that 2005 workshop in Bermuda. The Herald-Tribune's description of the meeting that led to the $82 billion financial impact beggars belief:Hurricane Katrina extracted a terrifying toll -- 1,200 dead, a premier American city in ruins, and the nation in shock. Insured losses would ultimately cost the property insurance industry $40 billion.

But Katrina did not tear a hole in the financial structure of America's property insurance system as large as the one carved scarcely six weeks later by a largely unknown company called Risk Management Solutions.

RMS, a multimillion-dollar company that helps insurers estimate hurricane losses and other risks, brought four hand-picked scientists together in a Bermuda hotel room.

There, on a Saturday in October 2005, the company gathered the justification it needed to rewrite hurricane risk. Instead of using 120 years of history to calculate the average number of storms each year, RMS used the scientists' work as the basis for a new crystal ball, a computer model that would estimate storms for the next five years.

The change created an $82 billion gap between the money insurers had and what they needed, a hole they spent the next five years trying to fill with rate increases and policy cancellations.

RMS said the change that drove Florida property insurance bills to record highs was based on "scientific consensus."

The reality was quite different.

I participated in the 2008 RMS expert elicitation, and at the time I explained that their methodology was biased and pre-determined. A group of monkeys would have arrived at the exact same results. Here is what I wrote then (and please see that post for the technical details on the "monkeys" making predictions, and the response and discussion with the RMS expert elicitor is here):The daily papers were still blaring news about Katrina when Jim Elsner received an invitation to stay over a day in Bermuda.

The hurricane expert from Florida State University would be on the island in October for an insurance-sponsored conference on climate change. One of the sponsors, a California-based company called RMS, wanted a private discussion with him and three other attendees.

Their task: Reach consensus on how global weather patterns had changed hurricane activity.

The experts pulled aside by RMS were far from representative of the divided field of tropical cyclone science. They belonged to a camp that believed hurricane activity was on the rise and, key to RMS, shared the contested belief that computer models could accurately predict the change.

Elsner's statistical work on hurricanes and climatology included a model to predict hurricane activity six months in advance, a tool for selling catastrophe bonds and other products to investors.

There was also Tom Knutson, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration meteorologist whose research linking rising carbon dioxide levels to potential storm damage had led to censoring by the Bush White House.

Joining them was British climate physicist Mark Saunders, who argued that insurers could use model predictions from his insurance-industry-funded center to increase profits 30 percent.

The rock star in the room was Kerry Emanuel, the oracle of climate change from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Just two weeks before Katrina, one of the world's leading scientific journals had published Emanuel's concise but frightening paper claiming humanity had changed the weather and doubled the damage potential of cyclones worldwide.

Elsner said he anticipated a general and scholarly talk.

Instead, RMS asked four questions: How many more hurricanes would form from 2006 to 2010? How many would reach land? How many the Caribbean? And how long would the trend last?

Elsner's discomfort grew as he realized RMS sought numbers to hard-wire into the computer program that helps insurers set rates.

"We're not really in the business of making outlooks. We're in the business of science," he told the Herald-Tribune in a 2009 interview. "Once I realized what they were using it for, then I said, 'Wait a minute.' It's one thing to talk about these things. It's another to quantify it."

Saunders did not respond to questions from the Herald-Tribune. Knutson said if RMS were to ask again, he would provide the same hurricane assessment he gave in 2005.

But Emanuel said he entered the discussion in 2005 "a little mystified" by what RMS was doing.

He now questions the credibility of any five-year prediction of major hurricanes. There is simply too much involved.

"Had I known then what I know now," Emanuel said, "I would have been even more skeptical."

Elsner's own frustration grew when he attempted to interject a fifth question he thought critical to any discussion of short-term activity: Where would the storms go?

The RMS modelers believed Florida would remain the target of most hurricane activity. Elsner's research showed storm activity shifted through time and that it was due to move north toward the Carolinas.

But RMS' facilitator said there was not enough time to debate the matter, Elsner said. There were planes to catch.

In the end, the four scientists came up with four hurricane estimates -- similar only in that they were all above the historic average.

RMS erased that difference with a bit of fifth-grade math. It calculated the average.

Thus, the long-term reality of 0.63 major hurricanes striking the U.S. every year yielded to a prediction of 0.90.

Contrary to Elsner's research, RMS aimed most of that virtual increase at Florida.

On paper, it was a small change from one tiny number to another tiny number.

Plugged into the core of a complex software program used to estimate hurricane losses, the number rewrote property insurance in North America.

Risk was no longer a measure of what had been, but what might be. And for Floridians living along the Atlantic, disaster was 45 percent more likely.

RMS defended its new model by suggesting it had brought scientists together for a formal, structured debate.Elsner disputes that idea.

"We were just winging it," he said.

I have in the past been somewhat critical of RMS for issuing short-term hurricane predictions (e.g., see here and here and here). I don’t believe that the science has demonstrated that such predictions can be made with any skill, and further, by issuing predictions, RMS creates at least the appearance of a conflict of interest as many of its customers will benefit (or lose) according to how these predictions are made. . . .RMS has since that time apparently shelved its expert elicitation process. My experiences prompted me to write up a paper on near-term predictions such as those employed by RMS, and it was published in the peer-reviewed literature:

The RMS expert elicitation process is based on questionable atmospheric science and plain old bad social science. This alone should lead RMS to get out of the near-term prediction business. Adding in the appearance of a conflict of interest from clients who benefit when forecasts are made to emphasize risk above the historical average makes a stronger case for RMS to abandon this particular practice. RMS is a leading company with an important role in a major financial industry. It should let its users determine what information on possible futures they want to incorporate when using a catastrophe model. RMS should abandon its expert elicitation and its effort to predict future hurricane landfalls for the good of the industry, but also in service of its own reputation.

Pielke, Jr., R.A. (2009), United States hurricane landfalls and damages: Can one-to five-year predictions beat climatology?. Environmental Hazards 8 187-200, issn: 1747-7891, doi: 10.3763/ehaz.2009.0017At the same time that RMS was rolling out its new model in 2006, an RMS scientist was serving as a lead author for the IPCC AR4. He inserted a graph (below) into the report suggesting a relationship between the costs of disasters and rising temperatures, when in fact the peer-reviewed literature said the opposite.

This paper asks whether one- to five-year predictions of United States hurricane landfalls and damages improve upon a baseline expectation derived from the climatological record. The paper argues that the large diversity of available predictions means that some predictions will improve upon climatology, but for decades if not longer it will be impossible to know whether these improvements were due to chance or actual skill. A review of efforts to predict hurricane landfalls and damage on timescales of one to five years does not lend much optimism to such efforts in any case. For decision makers, the recommendation is to use climatology as a baseline expectation and to clearly identify hedges away from this baseline, in order to clearly distinguish empirical from non-empirical justifications for judgements of risk.

RMS earlier this year admitted that the inclusion of that graph was a mistake, as it could have been "misleading."

And, you might ask, how did that five-year "short term" prediction from RMS made for 2006-2010 actually pan out? As you can see below, not so good.

12 November 2010

Estimating the Costs of Universal Electrification

How much would it cost to provide basic energy access to everyone? Michael Levi points to a new paper that he co-authored where the answer -- to one significant digit -- is $100 billion per year:

We have critically reviewed estimates of the costs related to promoting energy access and provided a basis to compare the figures. Considering some of the gaps identified, we have provided an estimate based on full levelised costs as a means of capturing dimensions absent from other analyses. While recognizing the coarse nature of our analysis, we find that the annual cost of universal energy access ranges from USD 12 to 134 billion for electrification and from USD 1.4 to 2.2 billion for clean cooking. The total (electricity and cooking) reaches USD 14, 62, and 136 billion for the low, medium and high scenarios, respectively. We note the sensitivity of the estimates to the underlying assumptions. Still, providing an order of magnitude assumption and bringing further transparency to methodological approaches can help support decision making at an international level and underpin political aspirations.

The total cost of reaching universal access to modern energy services might be significantly higher than indicated by the published studies. Our higher estimate is perhaps more realistic and is still possibly low, due to the methodological inadequacies discussed. Thus, we believe that for the purposes of political discourse, the total cost figure for full access to energy over USD 100 billion per annum – and roughly 1.5 trillion in total to 2030 - is significantly larger than the most oft-cited figures. It remains a fraction of total estimated investment costs in energy-supply infrastructure which amounts to USD 26 trillion for the period 2008-2030 (IEA 2009b, 104), and excludes recurrent costs.

11 November 2010

Video of Purdue Event: Beyond "Climategate"

A streaming video from the event at Purdue University last week with me, Andy Revkin and Judy Curry is now available for viewing at this link. Enjoy!

Chris Huhne on Pragmatic Energy Policies

Speaking in China earlier this week, Chris Huhne, UK Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, provided an indication of just how much the debate over climate change policies has evolved. He explained that policies focused on decarbonizing energy supply are justified on a much broader and pragmatic base than simply concern about climate change:

The UK's commitment to a sustainable energy mix is motivated by growing evidence that climate change is a tangible threat.Huhne's comments are a sign that the debate is moving in a healthy direction.

But it is also driven by more pragmatic concerns.

The first is purely economic.

For too long, our national prosperity was tied to the financial wizards in the City of London.

Risk-taking casino capitalism replaced manufacturing and production, hollowing out our industrial heartlands and creating an economy that was overly dependent on the financial sector.

When the credit crunch struck, were hit hard. We have had to cut public spending to pay down our budget deficit.

In the face of fiscal austerity, is it clear that greening our economy is the best way build a more balanced economy – and to secure more sustainable growth. With thousands of jobs in whole new industries, it is one of the brightest prospects not just for economic recovery, but for growth.

The second reason for our low-carbon transition is security.

As an island nation with dwindling fossil fuel resources, we are increasingly reliant on imported energy. Our energy import dependence could double by 2020.

Energy security is a prime concern.

Our winters are nowhere near as cold as those in Beijing. Nor are our summers as hot as Sichuan.

But we depend on scarce natural resources to keep our people warm and our economy moving.

Regardless of the public consensus on climate change, it is clear that relying on increasingly rare fossil fuels is not a long-term option. We cannot be exposed to the risk of resource conflict. Nor can we afford to remain at the mercy of volatile fossil fuel markets.

Not only are we vulnerable to interruptions in supply, we are also exposed to fluctuations in price. Oil or gas price shocks could reverberate throughout our fragile economy, hampering growth.

A more sustainable supply of energy is not an expensive luxury. It is a critical component in our national and economic security.

We are committed to clean coal with carbon capture and storage. To new nuclear power without public subsidy. To a radical nationwide programme of energy saving.

And to improve drastically our uptake of renewable energy.

Because thanks to a decade of under-investment in renewables by previous governments, we have a lot of ground to make up.

10 November 2010

Mixed Messages from Munich Re

Earlier this week Munich Re called for action on climate change, while touting its green investments, explaining that the rise in costs due to hurricanes was due to only one factor:

[Since 1980] windstorm natural catastrophes more than doubled, with particularly heavy losses from Atlantic hurricanes. This rise can only be explained by global warming. . . [I]nnovative insurance solutions will be needed to bring about the necessary transformation within the energy sector, where investments are often only feasible with the backing of innovative insurance covers.Writing last year in the peer reviewed literature, Munich Re successfully replicated work that I have been involved in, reaching exactly the same conclusions that we did about hurricane losses in the Atlantic:

There is no evidence yet of any trend in tropical cyclone losses that can be attributed directly to anthropogenic climate change.Knowing some of the scientists at Munich Re, and having high respect for their work and integrity, I can only conclude that the marketing department is not talking to the research department. What else would explain such polar opposite messages? (In case you are curious, the messages in the peer reviewed research results are consistent with the state of the science on this subject. The other stuff is not.)

Still No War on Science

The Obama Administration has again been caught out playing politics with science, according to the Washington Post:

Nah, that can't be true. The politicization of science is something done only by one's political opponents. Yes, that sounds much better.

The oil spill that damaged the Gulf of Mexico's reefs and wetlands is also threatening to stain the Obama administration's reputation for relying on science to guide policy.One might be tempted to conclude that the politicization of science is a bipartisan affair.

Academics, environmentalists and federal investigators have accused the administration since the April spill of downplaying scientific findings, misrepresenting data and, most recently, misconstruing the opinions of experts it solicited.

The latest complaint comes in a report by the Interior Department's inspector general, which concluded that the White House edited a drilling safety report in a way that made it falsely appear that scientists and experts backed the administration's six-month moratorium on new deep-water drilling. The Associated Press obtained the report Wednesday.

The inspector general said the editing changes by the White House resulted "in the implication that the moratorium recommendation had been peer reviewed." But it hadn't been.

Nah, that can't be true. The politicization of science is something done only by one's political opponents. Yes, that sounds much better.

An Interesting Look at Energy Subsidies

At the Breakthrough blog, Jesse Jenkins has this interesting analysis of numbers provided by the IEA's WEO 2010 (emphasis added):

While I certainly support the IEA's calls to phase out fossil fuel subsidies -- excepting where those would expand the already deplorable share of the global population (about 2.4 billion) locked in energy poverty -- the IEA figures on energy subsidies are actually a stark reminder of the major cost gap that persists between fossil energy and costlier clean energy alternatives.The debate involving subsidies should not be about "subsidization or not," but rather: in what contexts do certain types of subsidies make sense? The former is a recipe for empty ideological debates, and addressing the latter requires some thoughtful policy analyses, with answers that are not always clear cut.

If renewables account for a 7% share of global energy energy demand, and recieve $57 billion in subsidies, that's $8.14 billion for each percentage share of global demand. In contrast, fossil fuels supply about 83% of the global energy mix (nuclear accounts for the remaining 6%, according to the IEA) and recieve $312 billion in subsidies, for $3.76 billion per percentage share of global energy supplied.

In other words renewables recieve more than double the subsidy rate per unit of energy supplied as fossil fuels. When you consider that hydropower, which rarely requires or recieves subsidy, accounts for the vast share of global renewable energy production, the relative subsidy rate for wind, solar and other renewables per unit of energy produced is much higher.

This is why I always come back to the urgent need to make clean energy cheap, in real, unsubsidized terms. Ending fossil energy subsidies will help level the playing field, but only real innovation to drive down price and improve performance for a full suite of clean energy technologies can ensure that a meaningful share of global energy demand can be supplied by low-carbon alternatives to fossil fuels.

B.A.N.A.N.A Logic

I'm not sure where I first heard it, but the idea of NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) taken to the extreme results in BANANA (Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone). BANANA logic is on full display by the well-meaning but misguided folks at the Sierra Club in its campaign to halt experimental efforts to deploy carbon capture and storage off of the US East Coast:

However, a more fundamental problem with the Sierra Club's stance can be found in the IEA's 2010 World Energy Outlook, which argues that coal power is going to expand in coming decades -- regardless of what happens in the US or even new energy and climate policies. The IEA further argues that CCS will have to be deployed to 75% of coal plants by 2035 if the world is going to be on target to reaching a 450 ppm stabilization target.

So if the Sierra Club is successful in slowing down CCS prototypes and experimentation, what will it get? Plenty of coal plants with no CCS! Some victory.

If the Sierra Club really wants to move beyond coal, than rather than campaigning to halt innovation in technologies that it objects to, it should be actively trying to accelerate innovation in technologies that it approves of, with the goal of developing energy supply options that can displace coal over the longer term. You can't beat something with nothing. BANANA logic leaves you with exactly what you'd guess it would.

Dear Friend,One might question the Sierra Club's Catch-22 logic in invoking the untested nature of a technology as a reason to oppose its testing.

New Jersey's coastal waters are in serious danger from a proposed coal project. Right now a Massachusetts company wants to build a coal energy and fertilizer plant here in NJ and bury carbon dioxide pollution under the sea floor. Sounds pretty crazy to me, how about you?

The coal plant, called PurGen, is proposed for Linden, NJ, where it would use an experimental technology to compress carbon dioxide waste. The waste would be pumped through a 138-mile pipeline and forced down into the seabed off the coast of Atlantic City…forever.

This unproven technology called carbon capture and sequestration has not been tested for "forever" or even long-term. This experiment would take place in the most densely populated region of the country. An accident could have disastrous effects on marine life, or worse. . .

However, a more fundamental problem with the Sierra Club's stance can be found in the IEA's 2010 World Energy Outlook, which argues that coal power is going to expand in coming decades -- regardless of what happens in the US or even new energy and climate policies. The IEA further argues that CCS will have to be deployed to 75% of coal plants by 2035 if the world is going to be on target to reaching a 450 ppm stabilization target.

So if the Sierra Club is successful in slowing down CCS prototypes and experimentation, what will it get? Plenty of coal plants with no CCS! Some victory.

If the Sierra Club really wants to move beyond coal, than rather than campaigning to halt innovation in technologies that it objects to, it should be actively trying to accelerate innovation in technologies that it approves of, with the goal of developing energy supply options that can displace coal over the longer term. You can't beat something with nothing. BANANA logic leaves you with exactly what you'd guess it would.

We're Serious This Time

Gordon Brown said the following in the lead-up to the Copenhagen climate conference last year:

There are now fewer than 50 days to set the course of the next 50 years and more. If we do not reach a deal at this time, let us be in no doubt: once the damage from unchecked emissions growth is done, no retrospective global agreement in some future period can undo that choice. By then it will be irretrievably too late.In advance of the Cancun climate conference in a few weeks, India's Jairam Ramesh says:

We are running out of time, Cancun is the last chance. The credibility of the climate-change mechanism is at stake.What I think he must mean is that Cancun is the last chance . . . until South Africa 2012, which will be the last chance until . . .

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)