[This is a guest post by Ben Pile.]

[This is a guest post by Ben Pile.]In September 2008, Oxfam published a report called

“Climate Wrongs and Human Rights: Putting people at the heart of climate-change policy”. At our UK-based blog

Climate Resistance, we were unconvinced already. Humans, by definition, cannot be at the heart of any eco-centric view of the world. Moreover, the climate issue has been adopted by one-time development agencies to instead emphasise not developing as the most ‘progressive’ course of action for the world’s poorest people.

In failing to tackle global warming with urgency, rich countries are effectively violating the human rights of millions of the world’s poorest people. Continued excessive greenhouse-gas emissions primarily from industrialised nations are – with scientific certainty – creating floods, droughts, hurricanes, sea-level rise, and seasonal unpredictability. The result is failed harvests, disappearing islands, destroyed homes, water scarcity, and deepening health crises, which are undermining millions of peoples’ rights to life, security, food, water, health, shelter, and culture. Such rights violations could never truly be remedied in courts of law. Human-rights principles must be put at the heart of international climate change policy making now, in order to stop this irreversible damage to humanity’s future.

We began looking at the claims made in the report, and tried to establish where they had come from. For a part-time, unfunded project such as the

Climate-Resistance blog, this proved to be simply far too time-consuming, and other things were happening, such as the UK’s Climate Change Bill, which was going (being shoved) through Parliament.

We began compiling a list of the claims made by Oxfam, with the intention of asking them what their bases had been. For instance, in the quote above, Oxfam say that scientific certainty exists about the relationship between the carbon emissions of industrialised countries and floods, droughts, hurricanes, sea-level rise, and seasonal unpredictability that they have, allegedly, produced. We didn’t think that this was an appropriate emphasis of “scientific certainty”. Where had it come from?

What attracted our attention most, however, was this claim

According to the IPCC, climate change could halve yields from rain-fed crops in parts of Africa as early as 2020, and put 50 million more people worldwide at risk of hunger. [Pg. 2]

We looked to see if it was true. All we could find in the IPCC report was this.

In other [African] countries, additional risks that could be exacerbated by climate change include greater erosion, deficiencies in yields from rain-fed agriculture of up to 50% during the 2000-2020 period, and reductions in crop growth period (Agoumi, 2003). [IPCC WGII, Page 448. 9.4.4]

Oxfam cite the IPCC, but the citation belongs to Agoumi. The IPCC reference his study properly:

Agoumi, A., 2003: Vulnerability of North African countries to climatic changes: adaptation and implementation strategies for climatic change. Developing Perspectives on Climate Change: Issues and Analysis from Developing Countries and Countries with Economies in Transition. IISD/Climate Change Knowledge Network, 14 pp. (

PDF).

There is only limited discussion of “deficiencies in yields from rain-fed agriculture” in that paper, and its focus is not ‘some’ African countries, but just three: Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. It is not climate research. It is a discussion about the possible effects of climate change. All that the report actually says in relation to the IPCC quote, is that,

Studies on the future of vital agriculture in the region have shown the following risks, which are linked to climate change:

• greater erosion, leading to widespread soil degradation;

• deficient yields from rain-based agriculture of up to 50 per cent during the 2000–2020 period;

• reduced crop growth period;

Most interestingly, the study was not simply produced by some academic working in some academic department, for publication in some peer-reviewed journal. Instead, it was published by The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). According to the report itself,

The International Institute for Sustainable Development contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change, measurement and indicators, and natural resource management. By using Internet communications, we report on international negotiations and broker knowledge gained through collaborative projects with global partners, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries and better dialogue between North and South.

Oxfam takes its authority from the IPCC. The IPCC report seemingly takes its authority from a bullet point in a paper published by

an organisation with a declared political interest in the sustainability agenda that was the brainchild of former Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in 1988. (Take note: Conservatives are often behind the advance of the sustainability agenda, in spite of claims that it’s a left-wing phenomenon).

That the IPCC is citing non-peer-reviewed, non-scientific research from quasi governmental semi-independent sustainability advocacy organisations must say something about the dearth of scientific or empirical research. The paper in question barely provides any references for its own claims, yet by virtue of merely appearing in the IPCC’s 2007 AR4 report, a single study, put together by a single researcher, becomes “consensus science”.

The situation is simply insane. The IPCC are cited as producers of official science, yet they often appear to take as many liberties with the sources they cite, as those who cite the IPCC – such as Oxfam – go on to do. To ask questions about this process is to stand against ‘the consensus’, to be a ‘denier’, and to be willingly jeopardising the future of millions of people, and inviting the end of the world.

The popular view of the climate debate and politics is that the IPCC and scientists produce the science, which politicians and policymakers respond to, encouraged by NGOs, all reported on by journalists. But as the seemingly unfounded claims about the Himalayan glaciers and the North African water shortages show, this is a misconception. Science, the media, government, NGOs and supra-national political organisations do not exist as sharply distinct institutions. They are nebulous and porous. They merge, and each influences the interpretation and substance of the next iteration of their own product. The distinction between science and politics breaks down in the miasma.

If this process could be mapped, it would be no surprise if it was discovered that the IPCC was found to be citing itself through citing NGOs and Quasi-NGOs, and other non-peer-reviewed, not scientific literature. This is the real climate feedback mechanism. Sadly, we have no time and no resources to undertake such a survey, as much as we’d like to.

But would it even be necessary to ‘debunk’ the IPCC in this way? Maybe not. We can deal with the arguments on their own terms, after all. We have argued on

Climate Resistance that whatever the evidence or strength of the science with respect to the claim that “climate change is happening”, the political argument about how to respond to climate change depends far too much on the claim that “failure to act” is equivalent to producing a disaster.

The problem with much of the argument emerging from the sustainability camp of this kind is that its premise is political, not scientific. That is to say that the ‘politics is prior’ to the science. It may well be the case that the region that the IISD study focussed on faces increased droughts, and that, historically, agricultural output in those regions vary as rainfall varies, and that rainfall is declining. But this is not the whole story.

If they are at all true, the claims made in the reports from the IISD and Oxfam, and perhaps the IPCC, are only significant if we assume that mankind is impotent to address the water problems they describe. But the North African region covered by the study has a coast, lots of sunshine, and a lot of land. Indeed, the same area is being considered for a huge solar-energy project that could power much of Europe and the region, and so its water problems could be answered by the development of large-scale desalination infrastructure. The only problem is capital. So it is somewhat ironic that the lack of capital available to provide such a project with momentum is not the subject of Oxfam’s report.

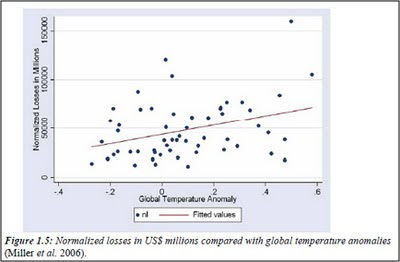

US-based consultancy, said the Stern report misquoted his work to suggest a firm link between global warming and the frequency and severity of disasters such as floods and hurricanes.