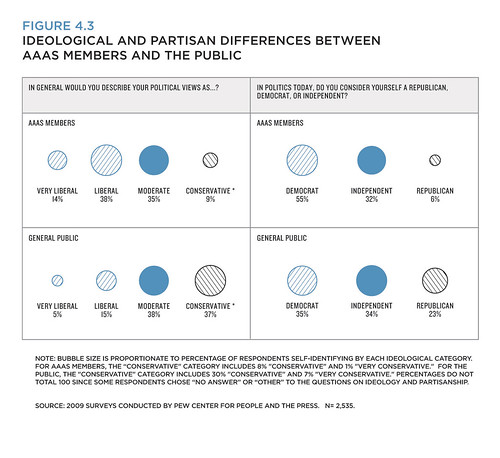

John Besley and Matt Nisbet have a new paper out (PDF) and a lengthy blog post summary in which they synthesize literature on how scientists in the US and UK view the public, the media and the political process. They end their review with a number of provocative hypotheses. On the skewed political self-identification of the US scientific community (skewed in relation to the broader public and as represented by the membership of the AAAS):

In the US data, for example, given the strong left-leaning political identity of scientists inMy personal experience over the past decade or so in the climate debate provides much first-hand evidence in support of this hypothesis. I provide a few examples in The Climate Fix of the strong professional pressure to not challenge certain views or institutions, based on political views or perceptions of political reception. (And a few juicy stories didn't make the cut;-)

the AAAS sample, moderates and conservatives among their ranks may feel reluctant to express political views, policy proposals or preferred public engagement approaches that are perceived as different from the preferences of their liberal counterparts.

Such pressure exhibits itself in less direct ways as well.

With an ever-increasing reliance on blogs, Facebook and personalized news, the tendency among scientists to consume, discuss and refer to self-confirming information sources is only likely to intensify, as will in turn the criticism directed at those who dissent from conventional views on policy or public engagement strategy. Moreover, if perceptions of bias and political identity do indeed strongly influence the participation of scientists in communication outreach via blogs, the media or public forums, there is the likelihood that the most visible scientists across these contexts are also likely to be among the most partisan and ideological.There is ample anecdotal evidence for such assertions, but it would be great to see some systematic studies. In particular, certainly worthy of further study is the way in which scientists and members of the public establish informal collaborations via social media such as blogs to intimidate or make uncomfortable those who would express challenging views. As is the case with respect to the public, the media and the political process most attention has been paid on how these groups affect the work of scientists (e.g., the entire issue of "scientific integrity" is about outside interference in the work of government scientists), which is certainly a very important topic. By contrast, very little scholarly attention (that I am aware of) has been focused on how scientists engage with the public, the media and the political process in an effort to enforce within the scientific community a particular political agenda (or a view of science perceived to be consistent with that agenda).

Besley and Nisbet summarize empirical analyses which provide for the arguments that I made in The Honest Broker, specifically, that as the scientific community has become more deeply engaged in policy issues that are debated among the public, there has been a tendency to see this engagement as a means of advocating for the special political interests of scientists. They write:

When it comes to policy debates, scientists recognize that they have a role to play in supporting public debate but emphasize a need to educate the public so that non-experts will make policy choices in line with the preferences of scientists.The scientific community thus has expressed some mixed and even conflicting views about their role in democratic systems (emphasis added):

As I have long argued, the best way for the scientific community to deal with the tide of politicization that it has been caught up in is not to try to remove itself from political debates, but rather to become more closely engaged -- but to do so intelligently. Understanding options for such intelligent engagement is the central challenge discussed in The Honest Broker.Scientists seem to walk a difficult line both in recognizing the right of citizens to play a role in

decision-making while having reservations about the public’s capacity to do so. One study spoke of a scientist’s need to have the public provide “legitimacy and validation” (Young and Matthews, 2007: 140). This position appeared to be operationalized as a duty to empower citizens to make good decisions. However, a good decision was understood as one that was consistent with scientists’ point of view, and empowerment was understood as education (Davies, 2008). In the end, scientists report feeling frustrated when they believe their views receive inadequate attention (Gamble and Kassardjian, 2008; Stilgoe, 2007).