We’re now at the first of October, and there’ve been no Category 3 or higher hurricanes (IH) to make landfall in the U. S. so far this season. The chances of a U. S. landfalling IH decrease significantly after 1 October. Over the past half-century, the only IHs to make landfall in the U. S. after 1 October were Hilda (1964), Opal (1995), and Wilma (2005). Hilda and Opal were already named tropical storms on the map as September ended—the only case forming in the month of October was Wilma.Even with the caveats, the US has had a remarkable streak of luck with respect to hurricanes -- or maybe, it's climate change! ;-)

If an IH does not make landfall in the U. S. during the remainder of this season, this will make five consecutive seasons without an IH landfall in the U. S. The last such instance of this (based upon the current HURDAT file) was 1910 – 1914. However, that being said, some caveats are in order.

(1) The current Saffir/Simpson classification of historical U. S. hurricanes was made by Hebert and Taylor in 1975. The parameter used to classify most of these was central pressure (CP), based on the older nominal CP ranges associated with each category. Nowadays, the S/S classification is based strictly upon the MSW at landfall.

(2) There are several cases, especially in the late 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s, for which the assigned S/S category does not match the Best Track winds, so when they are eventually re-analyzed, the landfalling category could be adjusted up or down.

(3) Hurricanes Gustav and Ike of 2008 both made their U. S. landfall with an estimated MSW of 95 kts, and with CPs of 957 and 952 mb, respectively. Had these storms occurred in the early 20th century, they would have been classified as Category 3 hurricanes, and barring any reliable wind measurements (which would have been unlikely) would have probably remained classified as such during the re-analysis. Similarly, though not within the past five years, Hurricanes Floyd and Isabel, which made landfall with an estimated MSW of 90 kts and CP around 956 mb, would have been classified as Category 3 hurricanes based on the CP.

30 September 2010

A New Hurricane Record?

Gary Padgett, writing to a tropical storm list-serv I am on, provides an interesting factoid, which I reproduce here with his permission (emphasis added):

Energy Access in Nigeria

Today's FT has a special report on Nigeria, and has a very interesting discussion of energy access:

The article has two very powerful quotes:

Despite average cash injections of $2bn annually over recent years and large untapped gas reserves, electricity capacity remains at about 40 watts per capita, roughly enough to run one vacuum cleaner for every 25 inhabitants.

China manages 466 watts per person, Germany 1,468. South Africa, the continent’s economic powerhouse, generates 10 times as much electricity as Nigeria for a population one-third the size.

Officials calculate that the potential activity stymied by lack of electricity amounts to $130bn a year.

In the absence of a functioning grid, those who can afford it, spend about $13bn a year running the small generators whose rattle and sputter is the soundtrack of urban life. The poorest 40 per cent have no access to electricity.

Banks estimate that spending on power drives up their costs by 20 per cent, helping push interest rates well beyond what small businesses can afford.

Potential investors are hardly filled with confidence when the lights go out at ministries or – terrifyingly – airports.

As Babatunde Fashola, Lagos state governor, said of the [Nigerian business conference] audience: “For them, electricity has become as important as oxygen.”And:

As if the audience needed reminding, the organisers added: “The cost of darkness is infinite.”

Let the Misrepresentation Begin

It was only a matter of time before the blogcritics engaged The Climate Fix, which I welcome. Unfortunately, they are off to a very bad start. William Connolley, formerly of Real Climate fame, accuses me of spreading lies:

[UPDATE 10/1: William Connolley has begrudgingly struck through a few words in his post, which I suppose indicates the minimal possible admission on his part that he was wrong. Even so, syndicated and unchanged versions of his post circulate in the blogosphere. I suspect that I'll see much more of this type of attack based on public discussions of The Climate Fix.]

Well, not quite direct lies, more in the nature of deliberately-misleading by omission.What is it that Connolley accuses me of omitting? It is part of a quote from Steven Schneider. Connolley explains, based on his reading of Greenberg's review in Nature:

There is a long-standing tradition of abusing this quote from Schneider: which means that neither RP Jr nor DG can have done it accidentally, which makes the abuse all the more surprising. If you don't know the context, the quote continues:The problem with Connolley's accusation is that I include the supposedly omitted quote in The Climate Fix and I also cite and quote from the APS Newsletter. All of this appears on pp. 202-203, and here is that discussion in full, and you can see clearly that Connolley is simply wrong in his accusation.

This 'double ethical bind' we frequently find ourselves in cannot be solved by any formula. Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and being honest. I hope that means being bothYou can find Schneider complaining about being misrepresented in this way by Julian Simon all the way back in 1996 in the APS newsletter.

Demands for certainty, however, don’t just come from politicians. Climate scientists also impose such demands on themselves, in order to make their scariest projections even scarier. This leads to more problems. In one of the more widely quoted comments ever made by a climate scientist, Steve Schneider wrote:I welcome engagement and criticisms from the blogosphere, but making things up and failing to do one's homework is pretty uncool.

On the one hand, as scientists we are ethically bound to the scientific method, in effect promising to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but—which means that we must include all the doubts, the caveats, the ifs, ands, and buts. On the other hand, we are not just scientists but human beings as well. And like most people we’d like to see the world a better place, which in this context translates into our working to reduce the risk of potentially disastrous climatic change. To do that we need to get some broad-based support, to capture the public’s imagination. That, of course, entails getting loads of media coverage. So we have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements, and make little mention of any doubts we might have. This “double ethical bind” we frequently find ourselves in cannot be solved by any formula. Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and bein honest. I hope that means being both.19For his part, Schneider emphasized that this double ethical bind should never be resolved by resorting to mischaracterizing uncertainties. In response to the frequent use of his quote to suggest a green light for alarmism, Schneider wrote, “Not only do I disapprove of the ‘ends justify the means’ philosophy of which I am accused, but, in fact have actively campaigned against it in myriad speeches and writings.”20 Indeed, the vast majority of climate scientists that I have had the pleasure to get to know and work with over the years shares Schneider’s passion for accurately conveying climate science to the public and placing it into its policy context. However, not all of their colleagues share this passion, coloring views of all of the climate-science enterprise.

[UPDATE 10/1: William Connolley has begrudgingly struck through a few words in his post, which I suppose indicates the minimal possible admission on his part that he was wrong. Even so, syndicated and unchanged versions of his post circulate in the blogosphere. I suspect that I'll see much more of this type of attack based on public discussions of The Climate Fix.]

29 September 2010

Daniel Greenberg on The Climate Fix in Nature

In the current issue of Nature, science policy polymath and well-known cynic Daniel Greenberg reviews The Climate Fix. Greenberg has some very positive things to say, upbraids me for my political naivete (showing his well earned role as dean of science policy cynics) and gets one big idea in the book very, very wrong.

First, the positive:

Finally, Greenberg introduces a serious misrepresentation of my views when he characterizes them as follows:

Ultimately, Greenberg concludes by emphasizing his own cynicism:

I fully accept his criticism that the book introduces nuance and common sense into a debate that welcomes neither. Greenberg's review is appreciated, however it is unfortunate that he badly mischaracterizes some of the major points in the book in as prominent a venue as Nature.

First, the positive:

Pielke merits admiration for his staunch defence of scientific accuracy and integrity. . . The author is well qualified to contest the established organs for addressing climate change, principally the IPCC and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. . . Pielke is not an apostle of inaction but a pragmatist who repeatedly and deservedly portrays his diagnoses and remedies as common sense.Second, the upbraiding:

[H]is well-argued book ignores political reality. Neither politicians nor the public respond to nuanced, cautiously worded messages from the arcane world of science. . . He largely fails to recognize, however, that common sense is frequently unwelcome in climate politics.. .If my book is too be criticized for its nuance and excessive common sense, well, I suppose I can live with that;-)

Finally, Greenberg introduces a serious misrepresentation of my views when he characterizes them as follows:

Although Pielke accepts that the evidence for human influence on the climate system is robust, he stresses that the goal of cutting global carbon emissions is incompatible with economic growth for the world's poorest 1.5 billion people.No. Not even close. In fact, I argue much the opposite -- it is through providing energy access to the world's poorest and sustaining economic growth that lies our best chance for decarbonization. This is the essence of the "oblique" approach that Chapter 9 focuses on. I can't imagine how Greenberg got this confused as I state it ad nausem, unless he skipped or skimmed over the last chapter. In the review he also confuses a carbon tax with a coal tax. He further mistakenly suggests that I see a focus on carbon dioxide as a tradeoff with adaptation, when again, I say the opposite, specifically that they are not substitutes for each other. Greenberg's expertise is not climate policy, but science policy, so that certainly explains his emphasis and perhaps his errors.

Ultimately, Greenberg concludes by emphasizing his own cynicism:

From where I sit, focusing on presenting politically acceptable policies built on a foundation of common sense is exactly what policy analysts and other experts should strive to do in the political process. I simply reject his implication that there is a trade-off between honesty and effectiveness, and say so in the book.The Climate Fix illustrates the dilemma confronting scientists who seek to influence politics. Telling it like it is does not thrive on Capitol Hill. But shaping the message to suit the politics often involves a betrayal of scientific truth and a distortion of public and political understanding.

I fully accept his criticism that the book introduces nuance and common sense into a debate that welcomes neither. Greenberg's review is appreciated, however it is unfortunate that he badly mischaracterizes some of the major points in the book in as prominent a venue as Nature.

Why Energy Efficiency Does not Decrease Energy Consumption

[NOTE: This is a guest post by Harry Saunders, cross-posted from The Breakthrough blog.]

Why Energy Efficiency Does not Decrease Energy Consumption

By Harry Saunders

I recently co-authored an article for the Journal of Physics ("Solid-state lighting: an energy-economics perspective" by Jeff Tsao, Harry Saunders, Randy Creighton, Mike Coltrin, Jerry Simmon, August 19, 2010) analyzing the increase in energy consumption that will likely result from new (and more efficient) solid-state lighting (SSL) technologies. The article triggered a round of commentaries and responses that have confused the debate over energy efficiency. What follows is my attempt to clarify the issue, and does not necessarily represent the views of my co-authors.

More Efficient Lighting Will Increase, Not Decrease, Energy Consumption

Our Journal of Physics article drew on 300 years of evidence to shows that, as lighting becomes more energy efficient, and thus cheaper, we use ever-more of it. The result, we note, is that "over the last three centuries, and even now, the world spends about 0.72% of its GDP on light. This was the case in the UK in 1700 (UK 1700), is the case in the undeveloped world not on grid electricity in modern times, and is the case for the developed world in modern times using the most advanced lighting technologies."

The implications of this research are important for those who care about global warming. In recent years, more efficient light bulbs have been widely viewed as an important step to reducing energy consumption and thus greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Moreover, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the United Nations and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have produced analyses that assume energy efficiency technologies will provide a substantial part of the remedy for climate change by reducing global energy consumption approximately 30 percent -- a reduction nearly sufficient to offset projected economic growth-driven energy consumption increases.

Many have come to believe that new, highly-efficient, solid-state lighting -- generally LED technology, like that used on the displays of stereo consoles, microwaves, and digital clocks -- will result in reduced energy consumption. We find the opposite is true, concluding "that there is a massive potential for growth in the consumption of light if new lighting technologies are developed with higher luminous efficacies and lower cost of light."

The good news is that increased light consumption has historically been tied to higher productivity and quality of life. The bad news is that energy efficient lighting should not be relied upon as means of reducing aggregate energy consumption, and therefore emissions. We thus write: "These conclusions suggest a subtle but important shift in how one views the baseline consequence of the increased energy efficiency associated with SSL. The consequence is not a simple 'engineering' decrease in energy consumption with consumption of light fixed, but rather an increase in human productivity and quality of life due to an increase in consumption of light." This phenomenon has come to be known as the energy "rebound" effect.

The Empirical Evidence for Rebound

The findings of our SSL research inspired The Economist magazine to write a commentary about the study that was mostly correct but made a couple of errors, which we responded to in a letter. In our response, we clarified that energy prices would need to increase 12 percent, not three-fold, in order to reduce the consumption of electricity for lighting, which, to its credit, The Economist posted on its web site and published in its letters section.

Evans Mills of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory wrote on the Climate Progress blog that The Economist had "inverted" our findings. However, The Economist did not "invert" our findings, it had simply overstated an implication of them.

Efficiency advocates sometimes dismiss rebound by only looking at "direct" energy consumption -- that is, consumption by households and for private transportation. Examples of rebound in this part of the energy economy would be driving your Prius more because gasoline costs you very little, or turning up the thermostat in your efficient home. But these "direct-use" rebounds are small in comparison to "indirect-use" rebounds in energy consumption. Globally, some two-thirds of all energy is consumed indirectly-- in the energy used to produce goods and services. A residential washing machine may be energy efficient in terms of function, but in terms of production, the metal body alone requires energy to mine, smelt, stamp, coat, assemble and transport it to a dealer showroom and eventually a residential home. The energy embedded in your washing machine, or just about any product or service you consume, is very large. And remember that any money you save on your energy bills through efficient appliances or the like is re-spent on other goods and services, which each take energy to produce, all while more productive use of our money (e.g. in spending, savings and production) spurs a more robust economy, demanding even more energy.

As our recent SSL research suggests, there is strong empirical evidence that even in the "direct" part of the economy, the rebound effect can sometimes be so substantial as to eliminate essentially all energy reduction gains. But in my new research (which relies on a detailed, theoretically rigorous econometric analysis of real data), the rebound effect found in the larger "indirect" part of the economy is even more significant -- and more worrisome.

Varying degrees of rebound occur because the phenomenon works in several ways. Increasingly efficient technologies effectively lower the cost of energy, as well as the products and services in which it is embedded. This results in firms consuming more energy relative to other production inputs and producing more output profitably. Firms and individuals benefit from cheaper and more abundant products and services, causing them to find many more uses for these (and the energy they contain). A more efficient steel plant, for example, produces cheaper steel that, in turn, allows firms and individuals to afford to find more uses for the same material.

While some find the notion that increased energy efficiency increases energy consumption to be counter-intuitive, the economic theory is remarkably commonsensical. Mills claims that the idea that the rebound effect "has been postulated in theory but never shown empirically to be significant" is not the case. After many years, rebound theory has advanced to the point that it is now a reliable foundation for empirical study and the empirical evidence firmly suggests rebound exists. And remember that the "rebound effect" for other factors of production is expected, even welcomed; economists have long expected labor productivity improvements to drive even greater economic activity, for example, thus increasing demand for labor and creating new employment opportunities in the economy as a whole, even as efficient production may eliminate a handful of jobs at one factory.

The Implications of Rebound

There are significant potential implications of high levels of rebound. One is that greater energy efficiency may be a net positive in increasing economic productivity and growth but should not be relied upon as a way to reduce energy consumption and thus greenhouse gas emissions. Particularly in a world where many billions lack sufficient access to modern energy services, efficient technologies such as solid-state lighting may be central to uplifting human dignity and improving quality of life through much of the world. One might even argue that energy efficiency is still important from a climate perspective, because when efficiency leads to greater economic growth, societies will be better able and more willing to invest in more expensive but cleaner energy sources. But in this way energy efficiency is no different from other strategies for increasing economic growth. What should be reconsidered is the assumption that energy efficiency results in a direct, net decrease in aggregate energy consumption when there is a growing body of research suggesting the opposite.

Dr. Harry Saunders has a B.S. in Physics from the University of Alberta, an M.S. in Resources Planning from the University of Calgary, and a Ph.D. in Engineering-Economic Systems from Stanford University. Saunders coined the "Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate" in 1992 to describe macro-economic theories of energy rebound, and has published widely on energy economics, evolutionary biology, and legal theory. He can be reached at: hsaunders@decisionprocessesinc.com.

Why Energy Efficiency Does not Decrease Energy Consumption

By Harry Saunders

I recently co-authored an article for the Journal of Physics ("Solid-state lighting: an energy-economics perspective" by Jeff Tsao, Harry Saunders, Randy Creighton, Mike Coltrin, Jerry Simmon, August 19, 2010) analyzing the increase in energy consumption that will likely result from new (and more efficient) solid-state lighting (SSL) technologies. The article triggered a round of commentaries and responses that have confused the debate over energy efficiency. What follows is my attempt to clarify the issue, and does not necessarily represent the views of my co-authors.

More Efficient Lighting Will Increase, Not Decrease, Energy Consumption

Our Journal of Physics article drew on 300 years of evidence to shows that, as lighting becomes more energy efficient, and thus cheaper, we use ever-more of it. The result, we note, is that "over the last three centuries, and even now, the world spends about 0.72% of its GDP on light. This was the case in the UK in 1700 (UK 1700), is the case in the undeveloped world not on grid electricity in modern times, and is the case for the developed world in modern times using the most advanced lighting technologies."

The implications of this research are important for those who care about global warming. In recent years, more efficient light bulbs have been widely viewed as an important step to reducing energy consumption and thus greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Moreover, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the United Nations and the International Energy Agency (IEA) have produced analyses that assume energy efficiency technologies will provide a substantial part of the remedy for climate change by reducing global energy consumption approximately 30 percent -- a reduction nearly sufficient to offset projected economic growth-driven energy consumption increases.

Many have come to believe that new, highly-efficient, solid-state lighting -- generally LED technology, like that used on the displays of stereo consoles, microwaves, and digital clocks -- will result in reduced energy consumption. We find the opposite is true, concluding "that there is a massive potential for growth in the consumption of light if new lighting technologies are developed with higher luminous efficacies and lower cost of light."

The good news is that increased light consumption has historically been tied to higher productivity and quality of life. The bad news is that energy efficient lighting should not be relied upon as means of reducing aggregate energy consumption, and therefore emissions. We thus write: "These conclusions suggest a subtle but important shift in how one views the baseline consequence of the increased energy efficiency associated with SSL. The consequence is not a simple 'engineering' decrease in energy consumption with consumption of light fixed, but rather an increase in human productivity and quality of life due to an increase in consumption of light." This phenomenon has come to be known as the energy "rebound" effect.

The Empirical Evidence for Rebound

The findings of our SSL research inspired The Economist magazine to write a commentary about the study that was mostly correct but made a couple of errors, which we responded to in a letter. In our response, we clarified that energy prices would need to increase 12 percent, not three-fold, in order to reduce the consumption of electricity for lighting, which, to its credit, The Economist posted on its web site and published in its letters section.

Evans Mills of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory wrote on the Climate Progress blog that The Economist had "inverted" our findings. However, The Economist did not "invert" our findings, it had simply overstated an implication of them.

Efficiency advocates sometimes dismiss rebound by only looking at "direct" energy consumption -- that is, consumption by households and for private transportation. Examples of rebound in this part of the energy economy would be driving your Prius more because gasoline costs you very little, or turning up the thermostat in your efficient home. But these "direct-use" rebounds are small in comparison to "indirect-use" rebounds in energy consumption. Globally, some two-thirds of all energy is consumed indirectly-- in the energy used to produce goods and services. A residential washing machine may be energy efficient in terms of function, but in terms of production, the metal body alone requires energy to mine, smelt, stamp, coat, assemble and transport it to a dealer showroom and eventually a residential home. The energy embedded in your washing machine, or just about any product or service you consume, is very large. And remember that any money you save on your energy bills through efficient appliances or the like is re-spent on other goods and services, which each take energy to produce, all while more productive use of our money (e.g. in spending, savings and production) spurs a more robust economy, demanding even more energy.

As our recent SSL research suggests, there is strong empirical evidence that even in the "direct" part of the economy, the rebound effect can sometimes be so substantial as to eliminate essentially all energy reduction gains. But in my new research (which relies on a detailed, theoretically rigorous econometric analysis of real data), the rebound effect found in the larger "indirect" part of the economy is even more significant -- and more worrisome.

Varying degrees of rebound occur because the phenomenon works in several ways. Increasingly efficient technologies effectively lower the cost of energy, as well as the products and services in which it is embedded. This results in firms consuming more energy relative to other production inputs and producing more output profitably. Firms and individuals benefit from cheaper and more abundant products and services, causing them to find many more uses for these (and the energy they contain). A more efficient steel plant, for example, produces cheaper steel that, in turn, allows firms and individuals to afford to find more uses for the same material.

While some find the notion that increased energy efficiency increases energy consumption to be counter-intuitive, the economic theory is remarkably commonsensical. Mills claims that the idea that the rebound effect "has been postulated in theory but never shown empirically to be significant" is not the case. After many years, rebound theory has advanced to the point that it is now a reliable foundation for empirical study and the empirical evidence firmly suggests rebound exists. And remember that the "rebound effect" for other factors of production is expected, even welcomed; economists have long expected labor productivity improvements to drive even greater economic activity, for example, thus increasing demand for labor and creating new employment opportunities in the economy as a whole, even as efficient production may eliminate a handful of jobs at one factory.

The Implications of Rebound

There are significant potential implications of high levels of rebound. One is that greater energy efficiency may be a net positive in increasing economic productivity and growth but should not be relied upon as a way to reduce energy consumption and thus greenhouse gas emissions. Particularly in a world where many billions lack sufficient access to modern energy services, efficient technologies such as solid-state lighting may be central to uplifting human dignity and improving quality of life through much of the world. One might even argue that energy efficiency is still important from a climate perspective, because when efficiency leads to greater economic growth, societies will be better able and more willing to invest in more expensive but cleaner energy sources. But in this way energy efficiency is no different from other strategies for increasing economic growth. What should be reconsidered is the assumption that energy efficiency results in a direct, net decrease in aggregate energy consumption when there is a growing body of research suggesting the opposite.

Dr. Harry Saunders has a B.S. in Physics from the University of Alberta, an M.S. in Resources Planning from the University of Calgary, and a Ph.D. in Engineering-Economic Systems from Stanford University. Saunders coined the "Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate" in 1992 to describe macro-economic theories of energy rebound, and has published widely on energy economics, evolutionary biology, and legal theory. He can be reached at: hsaunders@decisionprocessesinc.com.

Empty Debate and Climate Attack Dogs

Earlier this week, Andrew Turnbull, who was Cabinet Secretary under Tony Blair, had an op-ed in the Financial Times stating his views on the need for the climate science community to rebuild trust. Lord Turnbull's essay, written under his byline as a trustee of the Global Warming Policy Foundation, is fair and generally unremarkable.

He writes:

In a letter printed in today's FT, Bob Ward, a public relations specialist at the London School of Economics seeks to counter Lord Turnbull's arguments. The manner in which he chooses to do so illustrates how it is that debate over climate change has devolved to comical farce. The entirety of Ward's objections to Turnbull's arguments are that the GWPF has a flawed logo on its website and that Ward is unaware of GWPF funding sources.

I agree that the GWPF logo is flawed and my own policy views run counter to those of the GWPF. However, my judgments about trust in climate science have nothing to do with the GWPF choice of logos or their funding source. Even if they had a brilliant logo and money provided by Jeremy Grantham (whose generosity pays Mr. Ward's salary), I'd judge their policy recommendations as being flawed. Ward insults FT readers by suggesting that they should judge Turnbull's arguments not on their merits but by irrelevant distractions. Such is the state of climate debate in many quarters these days.

Ward's frequent efforts to reduce debate over climate change to tabloid-style mud wrestling is symptomatic of a debate that has lost touch with what matters. It is remarkable to me that an institution of higher learning such as LSE would hire a spin doctor to systematically engage in attacking reputations across the blogoosphere and letter pages of newspapers. Of course, when Bob does rarely engage in a public, scholarly debate, he is cordial and the attacks disappear. I am unaware of anyone playing an analogous PR "attack dog" role in a US academic context.

He writes:

To restore trust, it was essential that the government, parliament, the University of East Anglia and the Royal Society should respond quickly to get to the truth. They set up three inquiries but did those inquiries resolve the issues? A report by Andrew Montford for the Global Warming Policy Foundation shows serious flaws in the inquiries, which it says were marred by the failure to ensure independence in the panel members; by the refusal to take account of critical views; and by the failure to probe some serious allegations.Reasonable people can certainly debate whether or not the various UK inquiries succeeded in restoring confidence or not, and whether or not it would make sense for the new UK government to reopen these issues. My judgment is that the inquiries did not go very far in restoring trust among many, but at the same time, this situation does not justify a new set of investigations. At this stage, these are issues for the scientific community to deal with, not governments. So I disagree with Lord Turnbull's conclusions.

The result has been that the three investigations have failed to achieve their objective: conclusive restoration of confidence. In The Atlantic, Clive Crook of the Financial Times referred to “an ethos of suffocating group think”. That is exactly what the GWPF report revealed, with the investigators almost as much part of the group as the scientists.

The UK’s new parliamentary committee on science and technology needs to look again at how the inquiries were conducted to see if the exoneration claimed is merited. The government then needs to look at the serious criticisms of the IPCC made in the recent InterAcademy Council Report.

In a letter printed in today's FT, Bob Ward, a public relations specialist at the London School of Economics seeks to counter Lord Turnbull's arguments. The manner in which he chooses to do so illustrates how it is that debate over climate change has devolved to comical farce. The entirety of Ward's objections to Turnbull's arguments are that the GWPF has a flawed logo on its website and that Ward is unaware of GWPF funding sources.

I agree that the GWPF logo is flawed and my own policy views run counter to those of the GWPF. However, my judgments about trust in climate science have nothing to do with the GWPF choice of logos or their funding source. Even if they had a brilliant logo and money provided by Jeremy Grantham (whose generosity pays Mr. Ward's salary), I'd judge their policy recommendations as being flawed. Ward insults FT readers by suggesting that they should judge Turnbull's arguments not on their merits but by irrelevant distractions. Such is the state of climate debate in many quarters these days.

Ward's frequent efforts to reduce debate over climate change to tabloid-style mud wrestling is symptomatic of a debate that has lost touch with what matters. It is remarkable to me that an institution of higher learning such as LSE would hire a spin doctor to systematically engage in attacking reputations across the blogoosphere and letter pages of newspapers. Of course, when Bob does rarely engage in a public, scholarly debate, he is cordial and the attacks disappear. I am unaware of anyone playing an analogous PR "attack dog" role in a US academic context.

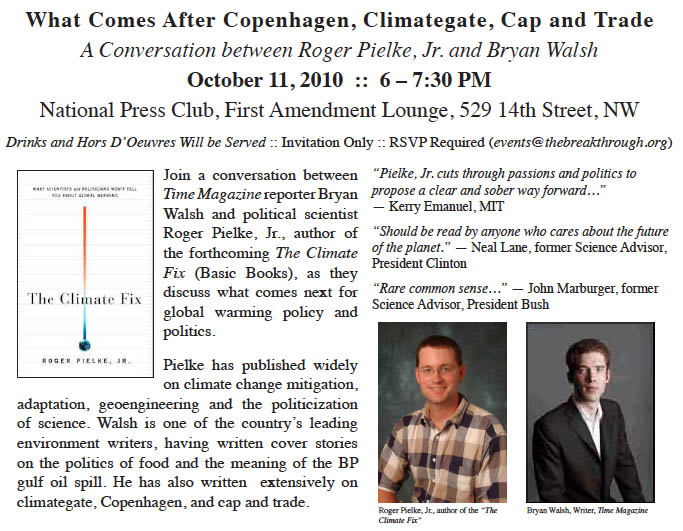

You Are Invited to an Invitation-Only Event

On October 11 in Washington, DC I will participate in a conversation with Bryan Walsh, of Time magazine at the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes. Drinks and snacks will be served. The event is "invitation only" but the organizers have said that it is OK for me to invite readers of this blog in the DC area to attend. You need only RSVP to events@thebreakthrough.org in order to secure a seat.

The event is co-sponsored by the Breakthrough Institute; Third Way; Yale Environment 360; the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University; the Said Business School at the University of Oxford; The Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado, Boulder; and the School of Communication at American University.

Details follow in the flyer below:

The event is co-sponsored by the Breakthrough Institute; Third Way; Yale Environment 360; the Consortium for Science, Policy and Outcomes at Arizona State University; the Said Business School at the University of Oxford; The Center for Environmental Journalism at the University of Colorado, Boulder; and the School of Communication at American University.

Details follow in the flyer below:

28 September 2010

This Just In -- Upcoming Debate with Benny Peiser

vs.

This just in -- I will be debating Benny Peiser of the Global Warming Policy Foundation in London on November 16th. The event will start at 5:30PM, so mark your calendars. I'll ask if it can be streamed or otherwise made available. I'll share further details as they are firmed up.

Exchange Between CO2scorecard.org and IEA

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Early this month I mentioned a report by the group CO2scorecard.org on apparent discrepancies in emissions reporting across different national and international agencies. CO2scorecard.org argued that "the empirical discrepancies in the current annual CO2 emissions estimates far exceed the annual reduction targets generally proposed by policy instruments like the cap‐and‐trade program or national commitments." That blog posting was followed by a behind-the-scenes discussion on CO2 data reporting between CO2scorecard.org and the IEA. With the permission of IEA, Shakeb Afsah of CO2scoirecard.org has asked if I'd post their exchange as a guest post. I am happy to facilitate an open exchange on this subject. The guest post follows. -RP]

Guest Post from CO2scorecard.org

First, I want to thank Roger and his blog visitors for their comments on our research note that discusses the issue of discrepancies in CO2 emissions numbers reported by various organizations worldwide. Our main goal was to highlight that differences in measurements and methodologies behind various CO2 numbers make it difficult to verify how well countries meet their annual reduction commitments (which are typically between 1-1.5% on an average annual basis). Various comments and ideas on this blog suggest a preference for using a policy indicator like the share of energy from carbon free sources that have fewer data quality concerns as opposed to estimating annual CO2 emissions. In our future research notes we plan to delve into such metrics in more detail.

We also want to share our email exchange with Ms. Karen Treanton of the International Energy Agency (IEA) because some of the concerns raised by the IEA gets to the heart of the methodological and data issues that we sought to amplify in our note. We would like to thank Roger for providing us this forum , and we look forward to your comments and hope that IEA would also participate if readers have questions.

Email from IEA: Dear Mr. Afsah, In principle I am not against your using our estimates of CO2 emissions from fuel combustion, but you really should use them correctly. The conclusions you draw on your website are misleading to say the least. We are completely transparent as to what we are including and how it is estimated. For example, we do not include fugitive CO2 emissions (IPCC source category 1B). Category 1B is included in the PBL and UNFCCC numbers – I do not know whether it is in the BP numbers. However, that would in part explain the lower numbers for the IEA. By ignoring the methodological differences you are creating confusion and throwing doubt on numbers that are actually more robust than you make them sound by saying: Experts assert, rightly, that perfectly consistent estimates of CO2 emissions are unattainable, but the current system is too flawed to be credible. Not only does it enable countries to fudge their actual emissions reductions, it has already resulted in some nasty political disputes. China recently challenged the energy use estimates of the IEA, calling it “not very credible.” If energy use data are challenged, it automatically raises concerns about national CO2 estimates. You refer to the problems that the Chinese had with IEA numbers. In fact, the IEA stands by its numbers. The Chinese were comparing energy balances for the US calculated by the Energy Information Adminstration in the US DOE (on a GCV basis) with the energy balances for China calculated by the Chinese government (on a NCV basis). That alone will make a large difference in the numbers but does not in any way cast doubt on the robustness of the numbers. In addition, the 2 balances were calculated using different assumptions for the primary energy equivalent for energy that is not combusted (i.e. hydro, solar, etc.) and China was not including non-commercial biomass. Having said that, none of these 3 differences would make a difference to the CO2 numbers that result from them if they are estimated correctly. Instead of helping the cause for reducing CO2 emissions, lack of transparency and proper notes might lead to the reverse effect, creating more trouble and giving more arguments to people who criticise the validity of facts and figures. This is why we would appreciate some revisions to your website. Before making a decision on providing you with additional information, I await your comments to my email. Regards. Karen Treanton Head of Energy Balances, Prices and Emissions Section Energy Statistics Division International Energy Agency |

CO2Scorecard.org’s Response: Dear Ms. Treanton, Thank you for your email and for sharing your concerns about the CO2 numbers we presented in our data discrepancies research note. We value feedback and constructive criticisms from experts like you, and accordingly we have taken a look at the adjustments to UNFCC’s CO2 numbers for IPCC Categories IB1 and IB2 for fugitive emissions. Our analysis shows that even after adjusting for fugitive emissions, which is around 0.4% for the US (EDGAR 4.1/2005 estimate), there is a difference of more than 100 million tons between IEA and UNFCCC numbers for the year 2006. Therefore our central conclusion about CO2 discrepancies remains unchanged. If we price CO2 at around $10 per ton, this discrepancy would be worth more than a $ 1 billion. In our view it is a sizeable amount that deserves some policy attention. Regarding your comment about our reference to the reaction from China about the IEA energy use estimates, our main goal is to simply highlight that the differences in the CO2 and energy use numbers from data reporters are a potential source of dispute. We are simply citing what was reported in the Financial Times. Further, we respectfully disagree with your statement that we are not helping the cause of CO2 emissions reduction. On the contrary, a healthy debate on data quality issues for CO2 numbers is precisely what is needed to ensure that as we move forward with various policy options, we also build a good capacity to monitor and verify CO2 reductions. We believe that there is a genuine issue of discrepancies and inconsistencies across CO2 and energy use data reporters—each organization may be right in the choice of their methodologies but there is a need for further harmonization and increased transparency. We would also urge IEA to release its estimates of CO2 emissions for the years 2008 and 2009 which are currently available only on a commercial basis. Despite our differences of opinion on this issue, we look forward to continuing a dialogue with you and your colleagues at the IEA regarding current methodologies for measurement of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions around the world. We also hope to engage other leading reporting authorities in a similar dialogue. We would also strongly encourage a common conversation among reporting authorities for national-level energy and emissions data regarding potential avenues for harmonization of standards to aid in the comparability of estimates from different data reporting sources. Thank you very much and please don't hesitate to contact us if you have any questions regarding this response. Regards Shakeb Afsah and Michael Aller The CO2 Scorecard Group Bethesda, MD |

Follow Up: Extension of Spanish Coal Subsidies to be Approved by EU

Last week I commented on a pending EU decision on Spain's desire to increase subsidies for domestic coal production. According to news reports, the EU is going to rule in favor of coal:

Spain will win EU approval this week to double aid to its coal industry until the end of 2014, despite criticism from environmentalists and the Spanish watchdog, three people with direct knowledge of the case said on Monday.The implications for EU carbon policies are clear -- grant us decarbonization, just not yet.

Spain will also have slightly more time to phase out aid than other EU countries, which have until October 15, 2014.

The decision by the European Commission (EC), the EU competition watchdog, comes amid strikes by Spanish coal miners demanding unpaid wages and EU approval of the plan to let Spain favor domestic coal over imports.

"The Commission will say that subsidies should not go beyond December 31, 2014," one of the people said.

Opponents within the EC are seeking to close any loopholes that could allow Spain to extend this aid beyond 2014.

"Some commissioners are seeking to ensure a political assurance from Spain that this will not be extended beyond 2014," said a second person.

The European Union executive will announce its decision on Wednesday, when Spanish miners hold their second 48-hour strike, which also coincides with a nationwide general strike, part of a wave of unrest to hit Europe this autumn.

Spain's competition regulator has criticized the aid, saying it would distort the power market. The scheme forces power plants to burn more expensive domestic coal, which utilities say will increase prices.

27 September 2010

Me on Geoengineering on Southern California Public Radio

I was interviewed this morning by Madeline Brand on Southern California Public Radio on the subject of geoengineering. I discuss geoengineering in Chapter 5 of The Climate Fix. In the interview I try to give a fair account, but I am decidedly not a fan. My interview can be accessed at the link above and it is the top one of the two audio links.

Munich Re Goes too Far

Munich Re, the global resinurance company, has always had a complicated relationship with the science of disasters and climate change due to the emission of greenhouse gases. On the one hand, its technical staff have published solid work in the peer reviewed literature. On the other hand, its marketing statements often go beyond what the science can support.

Today, Munich Re went way over the line when it issued a highly misleading press release attributing disasters in 2010 to climate change. The press release is titled:

The press release concludes with this statement:

Today, Munich Re went way over the line when it issued a highly misleading press release attributing disasters in 2010 to climate change. The press release is titled:

Two months prior to Cancun Summit/Large number of weather extremes as strong indication of climate changeThe text of the press release would seem to suggest that Munich Re can't back up this claim, other than with empty speculation (emphasis added):

The rise in natural catastrophe losses is primarily due to socio-economic factors. In many countries, populations are rising, and more and more people moving into exposed areas. At the same time, greater prosperity is leading to higher property values. Nevertheless, it would seem that the only plausible explanation for the rise in weather-related catastrophes is climate change. The view that weather extremes are more frequent and intense due to global warming coincides with the current state of scientific knowledge as set out in the Fourth IPCC Assessment Report.The press release then goes on to list a number of phenomena that it asserts are being driven by climate change:

There are at present insufficient data on many weather risks and regions to permit statistically backed assertions regarding the link with climate change.

[T]here is evidence that, as a result of warming, events associated with severe windstorms, such as thunderstorms, hail and cloudbursts, have become more frequent in parts of the USA, southwest Germany and other regions. The number of very severe tropical cyclones is also increasing. One direct result of warming is an increase in heatwaves such as that experienced in Russia this summer. There are also indications of a higher incidence of atmospheric conditions causing air mass formation on the north side of the Alps and low-lying mountain ranges, a phenomenon which can result in floods. Heavy rain and flash floods are affecting not only people living close to rivers but also those who live well away from traditionally flood-prone areas.The actual state of the science is that no connection has been shown between greenhouse gas emissions and thunderstorms, tropical cyclones, Russian heatwaves or European floods. Regrettably, Munich Re has made a jump from making a tenuous assertion to propagating incorrect information.

The press release concludes with this statement:

In the two months preceding the World Climate Summit, Munich Re will be drawing attention to the climate change issue with a series of communications and publications. The ERGO Insurance Group and MEAG, the asset manager of ERGO and Munich Re, are also planning to issue press releases in the next few weeks on insurance products related to natural catastrophes and renewable energy as well as business activities designed to reduce carbon emissions.Enough said.

Establishing Credibility via Acknowledging Uncertainties and Ignorance

On Saturday, the NYT had an interesting analysis of a new approach to presenting uncertainties to the public:

During the Bush administration, the Food and Drug Administration was mostly a place of black-and-white decisions. Drugs were approved for sale or they were not, and the agency’s staff was expected to publicly support those decisions.Being open about uncertainties, the contested views of experts and how these factors play into decision making can help to establish the legitimacy of FDA decision making. Ironically enough, more knowledge can actually mean greater uncertainties:

But as Thursday’s landmark decision on the controversial diabetes medicine Avandia makes clear, things have changed under the Obama administration. Certainty, staff unanimity and even the approval status of big-selling medicines are no longer so black and white.

Presented with what seemed to be a choice between keeping Avandia on the market or withdrawing it, the Obama administration decided on an unusual middle path — allowing sales, but with tight restrictions. Even more unusually, the agency admitted that many of its top scientists disagreed, some passionately. Competing memorandums were posted immediately on the agency’s Web site.

And the agency’s three top officials co-wrote a highly unusual explanation of their action in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Some of these changes have been in the works for years, but they have accelerated under the Obama administration, driven by increasingly sophisticated measures of drug safety and growing skepticism about whether the F.D.A. is making the right decisions and making them appropriately.

“I think that F.D.A.’s credibility really depends on being able to explain its decisions well,” said Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, F.D.A.’s principal deputy commissioner. “We can’t expect people to think that F.D.A. has decided, therefore it’s the right answer.”

“In the past, we would approve the drug after a couple of efficacy trials and that was it,” Dr. Janet Woodcock, chief of the F.D.A.’s drug center, said in an interview. “We didn’t know too much more about the drug. It was simpler.”Effective science arbitration is a complex process that goes well beyond "just the facts" or even establishing a consensus view.

Now, sophisticated analyses present the F.D.A. with a complex picture. “It’s good for public health that we’re learning more, but it creates a more complex environment in which to regulate,” Dr. Woodcock said.

It is an environment in which top agency officials are in some ways at sea. The agency has no systems or standards to follow in deciding which studies deserve their attention or should lead to changes in a drug’s status. And since new tests are being created constantly, creating such a standard would be an ever-evolving process.

Dr. Lynn Goldman, dean of the School of Public Health and Health Services at George Washington University, said the F.D.A. was being forced to become more comfortable with studies done in academic rather than regulatory settings. “They have to get used to a less controlled environment,” Dr. Goldman said.

This Can't be Sustainable

The WSJ reports that 5 MLS players receive about 30% of the league's entire payroll:

David Beckham and Landon Donovan of the Galaxy and Rafael Marquez, Juan Pablo Angel and the injured Thierry Henry of the Red Bulls make a combined $21.7 million in guaranteed compensation from their clubs. This represents about 30% of the entire league payroll of $71.3 million, according to MLS Players Union figures. In fact, those five players combine to make nearly four times as much as the entire team with the next-highest payroll, the Chicago Fire. And Messrs. Henry and Beckham individually make more than every team except their own. Mr. Beckham, with a $6.5 million salary, makes more than the combined payrolls of the New England Revolution and defending champs Real Salt Lake.MLS won't become a serious second tier league until it can do more than pay high salaries to aging former superstars.

24 September 2010

Foot Drain

Here is an interesting BBC story from the poorly researched subject of the international transfer of footballers:

According to a report from sports marketing consultancy Euroamericas, it has replaced Brazil as the country exporting the most professional players to European and Arab football leagues.

Argentina sold more than 1,700 players last year, almost 300 more than Brazil.

Argentina's trade has grown by almost 800% in five years after European clubs eased restrictions on foreign players.

Last year the football player export business was worth $117m (£74.5m) to Argentina.

A total of 1,716 Argentine players were sold, compared with 1,443 sold by the next biggest provider, Brazil.

Analysts say this is the result of Argentine clubs developing strategies to get funds by selling young players as early as possible in their careers.

Critics say that by selling teenage players before they have even made their local debut will compromise the quality of Argentina's main domestic league in the near future.

IPCC on Extreme Events: Getting Better but Still Not Great

Yesterday, Michael Oppenheimer from Princeton University and coordinating lead author of the IPCC special report titled Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, provided a briefing to the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming of the US House of Representatives (here in PDF). Oppenheimer's testimony was far more in line with the state of the science on this subject than have been recent IPCC reports and press releases, but remains slanted and focused on advocating action on emissions.

Oppenheimer states:

Oppenheimer's conclusion acknowledges the importance of societal factors in driving disasters, but then completely ignores adaptation (which he does mention elsewhere in the presentation), which indicates to me that the desire to advocate among IPCC leaders will be a habit hard to control:

If I had to give a grade to the presentation -- if the IPCC 2007 was an "F," then Oppenheimer gets a "C-." The IPCC leadership still has a ways to go on the issue of extreme events. Its extremes report is not due out for another year (remarkably), so they have lots of time to up their game.

Oppenheimer states:

So-called “joint attribution” the assignment of cause for the damaging outcomes of such extremes, such as wildfires or human mortality occurring during hot and dry spells, is a relatively new field, and it remains difficult to associate recent increases in most such impacts directly with greenhouse gas emissions, but indirect evidence is strongly suggestive of such a link in many cases.This is a convoluted way of simply saying that the present state of the science does not support claims of attribution. In suggesting that this is a "new" field he notably avoids discussing a large body of literature such as on tropical cyclones (in the US, Australia, China, India, Latin America, etc.), floods, European storms, Australian bushfires, etc. where peer reviewed work has explained damage trends solely in terms of increasing societal vulnerability. Why is it so hard for IPCC authors to acknowledge any of this literature? But, even so, I give Opeenheimer some credit for moving in the right direction.

Oppenheimer's conclusion acknowledges the importance of societal factors in driving disasters, but then completely ignores adaptation (which he does mention elsewhere in the presentation), which indicates to me that the desire to advocate among IPCC leaders will be a habit hard to control:

Finally, while extreme events are generally a physical phenomenon, circumstances where such events translate into disasters, like Hurricane Katrina or the great European heat wave of 2003, depend in large measure on individual and societal anticipation, planning, and response capacity and implementation. In other words, disaster is partly a social phenomenon. In both of these episodes, the toll was much higher than was imagined possible before the events. Unfortunately, if history is a guide, such situations may become ever more common. Even as we learn to cope better with certain extreme events, the climate may change faster than we learn about it, and faster than our ability to implement what we have learned. The only remedy for such a situation is to act to slow the climate change by slowing greenhouse gas emissions.Oppenheimer's statement is a move in the right direction, but it is highly selective, slanted and gives some misleading policy advice. The reality is that actions today to reduce emissions will not have an discernible effects for many decades. By not mentioning the time scale of the effects of mitigation and the relative role of mitigation and adaptation for addressing future losses (another literature not mentioned), Oppenheimer is arguably misleading.

If I had to give a grade to the presentation -- if the IPCC 2007 was an "F," then Oppenheimer gets a "C-." The IPCC leadership still has a ways to go on the issue of extreme events. Its extremes report is not due out for another year (remarkably), so they have lots of time to up their game.

Prins on Hartwell at the EBR

In the European Business Review Gwyn Prins provides a condensed interpretation of The Hartwell Paper. I have received a few requests for capsule summaries, and Gwyn's is pretty good.

23 September 2010

A Carbon Tax Back in Play Down Under

Australia's politics over climate policies continue to churn. From ABC News:

Climate Change Minister Greg Combet has given a clear sign the Federal Government is prepared to consider introducing a carbon tax.

Before the election, Prime Minister Julia Gillard ruled out using a tax to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But the Greens advocate a tax as an interim measure and the chief of BHP has also endorsed the idea.

Mr Combet says the Government is determined to put a price on carbon and the new parliamentary committee on climate change will consider all options.

"In the political reality in the formation of the Government, the circumstances are a bit different than we anticipated," he said.

"It does mean that alternative policy options will come onto the table; we will be looking at the various options for the development of a carbon price as I said and we'll thoroughly subject them to proper evaluation.

"Things will be stress tested, the proper modelling and work and expert advice will be done, but serious work will be performed to try to develop the best possible option for this economic reform."

Job Security for Partisan Climate Bloggers

E&E Daily reports that Representative Darrell Issa (R-CA) has said that should the Republicans take over the House, they will open up investigations into the release of the East Anglia emails:

The House's top Republican watchdog is planning to launch an investigation into international climate data if he takes the helm of the chamber's oversight panel next year.If one wanted to improve the quality of numbers, then doing so via a highly partisan congressional investigation is probably not the best way to go about it. On the flip side, the most partisan climate bloggers will have plenty of exciting new material to fight with each other about. (H/T: DS)

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), the ranking member of the Oversight and Government Reform Committee, said a probe of the "Climategate" scandal will top his environmental agenda if the Republicans take over the House next year and he gets the chairmanship.

"I do have a backburner investigation that I'm going to want to have completed, and that is, we paid a lot of money to have international evaluation, most of it done in Britain, that turns out to have been less than truthful in some of the figures," he said. "We're going to want to not investigate to get our money back, but we're going to want to have a do-over of good numbers so that everyone can have confidence."

From the Comments: Werner Krauss on Democracy

In the comments responding to my post about German politics and energy policies, Werner Krauss provided this eloquent comment on the virtues of democracy:

Energy plans are colliding with cultural realities. Nothing new. You need a lot of nerves in democratic processes. We are so used to analyze the world in left - right / green - brown / black & blue, or whatever: in reality it doesn't work all the time. There is a permanent transformation going on which ridicules many analysts. Social democrats, conservatives, greens have to permanently reinvent themselves. Sure, it is dangerous and discomforting when normal compasses don't work (and populists come up and fill the gap). But democracy needs trust, especially in times of profound energy transformations. Angela Merkel does her deal with the nuclear lobby; the protest movement will challenge her. It's a good thing: there is a lot at stake, and its a form of negotiating in public.

22 September 2010

Access to Energy, Poverty Alleviation and Policy Blinders

The NYT has a story today on a new report from the IEA (here in PDF) issued in conjunction with a meeting of the UN general Assembly:

This is a shame, because the best path forward to accelerating decarbonization of the global economy lies not in pretending that a conflict does not exist between poverty alleviation and emissions reductions, but precisely the opposite. The only way that we will meet the world's energy needs of the future -- especially the needs of the 1.5 billion lacking access -- is to diversify and reduce the cost of energy via a commitment to innovation.

When we put on policy blinders to avoid seeing things we'd rather not, sometimes the result is that we miss out on seeing some pretty important things as well.

More than $36 billion a year is needed to ensure that the world’s population benefits from access to electricity and clean-burning cooking facilities by 2030, the International Energy Agency said Tuesday.But as anyone who understands the Kaya Identity knows, bringing people out of poverty will necessarily lead to greater greenhouse gas emissions. Birol tries to sidestep this issue:

In a report prepared for the United Nations Millennium Development Goals meeting in New York, the agency said the goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2015 would be possible only if an additional 395 million people obtained access to electricity and one billion gained access to more modern cooking facilities that minimize harmful smoke in the next few years.

“Without electricity, social and economic development is much more difficult,” Fatih Birol, the energy agency’s chief economist, said by telephone. “Addressing sanitation, clean water, hunger — these goals can’t be met without providing access to energy.”

The problem of energy inequality mirrors the gap between rich and poor countries, Mr. Birol said. “The amount of electricity consumed by sub-Saharan Africa, with 800 million people, is about the same as that used in New York State, with about 19 million people,” he said.

I have discussed these estimates before, and they simple to not stand up to the most basic of arithmetic. As I wrote last November, when I critiqued a similar statement from Birol:

Mr. Birol played down concerns that bringing more of the global population into the modern energy economy would be bad for the environment.

He predicted that meeting the development goal would raise global oil consumption just 1 percent, while raising carbon emissions only 0.8 percent.

[T]he IEA is arguing that electricity can be provided to 1.3 billion people by 2030 and it will add only 0.24 GtCO2. Somehow I don't find that to be credible.I understand what Birol is trying to do -- he wants to avoid any perception that poverty alleviation comes into conflict with efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. So he is arguing that you can lift people from poverty with almost no effect on carbon dioxide emissions. This argument is just wrong. While this argument allows the poverty alleviation and carbon dioxide reduction agendas to seemingly co-exit harmoniously, it dramatically downplays the challenge of emissions reductions.

By contrast, if each of those 1.3 billion people had average emissions at the 2007 world average of 4.4 tCo2 they would add about 5.72 GtCO2 to the 2030 total, or an increase of 14% over the [450 ppm stabilization] Reference Scenario.

What this exercise shows is that you can have a lot of fun with Reference Scenarios and Stabilization Scenarios, none of which is too closely connected to the real world. To suggest that access to electricity for 1.3 billion people can be provided at a marginal emission increase of 0.24 GtCO2 is misleading at best, and yet another example of how international assessments serve to dramatically understate the magnitude of the decarbonization challenge.

This is a shame, because the best path forward to accelerating decarbonization of the global economy lies not in pretending that a conflict does not exist between poverty alleviation and emissions reductions, but precisely the opposite. The only way that we will meet the world's energy needs of the future -- especially the needs of the 1.5 billion lacking access -- is to diversify and reduce the cost of energy via a commitment to innovation.

When we put on policy blinders to avoid seeing things we'd rather not, sometimes the result is that we miss out on seeing some pretty important things as well.

The Attraction of Populist Politics in Germany

Democracy is about giving people what they want, right? And if the political leaders aren't giving the people what they want, then surely opposition leaders should fill the gap?

Across Europe and the United States, politicians and policy wonks are getting a harsh lesson in democratic politics. For instance, in Sweden's election over the weekend, a lurch to the right has a party with neo-Nazi roots holding the balance of parliamentary power, a change driven by concerns about immigration. The US has seen its own political insurgency in the form of the Tea Party movement.

Germany has not been immune to such issues, including its own conflicts over immigration, fueling the far right. With respect to energy policy I recently and approvingly discussed Angela Merkel's negotiated agreement to extend the life of Germany's nuclear power plants, using the resulting windfall to invest in clean energy innovation. This agreement is now at risk, due to the harsh realities of populist politics.

Following a protest against the nuclear extension plan over the weekend in Berlin involving more than 100,000 people, opposition leader Sigmar Gabriel, leader of the Social Democrats, has seized on hte opportunity to gain political advantage. He says:

His call for a referendum is significant, because Germany doesn't do referenda:

What is the lesson to take from the current politics in Germany (and elsewhere)? Even the best laid policy plans are of little use unless they account for the politics of the day and are robust enough to survive the inevitably changing politics of the future. One obstacle to implementing improved energy policies (that is, those that expand access, reduce cost, and increase security while fostering accelerated decarbonization as a valuable ancillary benefit) is that policy analyses too often ignore unyeilding political realities.

From my vantage point it looks like Merkel's nuclear plan is in deep trouble. Did it have to be?

Across Europe and the United States, politicians and policy wonks are getting a harsh lesson in democratic politics. For instance, in Sweden's election over the weekend, a lurch to the right has a party with neo-Nazi roots holding the balance of parliamentary power, a change driven by concerns about immigration. The US has seen its own political insurgency in the form of the Tea Party movement.

Germany has not been immune to such issues, including its own conflicts over immigration, fueling the far right. With respect to energy policy I recently and approvingly discussed Angela Merkel's negotiated agreement to extend the life of Germany's nuclear power plants, using the resulting windfall to invest in clean energy innovation. This agreement is now at risk, due to the harsh realities of populist politics.

Following a protest against the nuclear extension plan over the weekend in Berlin involving more than 100,000 people, opposition leader Sigmar Gabriel, leader of the Social Democrats, has seized on hte opportunity to gain political advantage. He says:

"Angela Merkel's nuclear deal is driving people into the streets because it is a stimulus program for political disaffection when the head of a government cuts a backroom deal with four energy bosses that's worth hundreds of billions of euros and safety issues for old nuclear plants are sorted out on the side," Gabriel said. "Those dealings should all be public. ... It would be best if the people could vote on the lifespan extension in a referendum."Gabriel knows which way the winds are blowing, and not surprisingly, has also called for tighter restrictions on immigration.

His call for a referendum is significant, because Germany doesn't do referenda:

Recent opinion surveys suggest the [nuclear extension] decision is opposed by a clear majority of German voters, with 59 per cent against compared with 37 per cent in favour, according to a poll conducted by Infratest dimap for the ARD state television station. If voters can be persuaded that such a move would save jobs, or help finance renewable energy in the long run, a majority would be in favour.But if not nuclear then what? Gabriel has answered that question as well (hint: it is black and dirty).

The opposition parties see the policy as fundamentally unpopular and expect to win substantial support for a revived anti-nuclear campaign. In an interview with Spiegel magazine, Renate Künast, joint parliamentary leader of the Greens, said they would use “all means possible – legal challenges, demonstrations and election campaigns”, to make sure the extension was not approved.

Mr Gabriel’s proposal for a national referendum seems designed more as a tactical move to shock the political establishment than a likely way of blocking the plan. Referendums are barred under the German constitution on the grounds that they undermine parliamentary democracy – and contributed to the rise of the Nazi party in the 1930s.

What is the lesson to take from the current politics in Germany (and elsewhere)? Even the best laid policy plans are of little use unless they account for the politics of the day and are robust enough to survive the inevitably changing politics of the future. One obstacle to implementing improved energy policies (that is, those that expand access, reduce cost, and increase security while fostering accelerated decarbonization as a valuable ancillary benefit) is that policy analyses too often ignore unyeilding political realities.

From my vantage point it looks like Merkel's nuclear plan is in deep trouble. Did it have to be?

The End of Spanish Coal Subsidies?

Spain has sparked a row with Brussels over extending state subsidies for its coal industry. Spanish miners are engaging in public protests and strikes, putting pressure on the Spanish government to save their jobs from an EU plan to end coal subsidies. The EU is set to rule next week on the Spanish plan to extend and increase domestic subsidies for the coal industry. The FT reports:

Efforts by Brussels to end state aid to uneconomic coal mines could be damaged if the European Commission gives the go-ahead to a separate Spanish government plan that would double aid to the country’s coal-mining sector, European Union officials have been warned.The Wall Street Journal argues that the time is right to end the wasteful state subsidies:

The controversial Spanish plan, which could cost billions of euros during the next four years, centres on giving preferential access to the wholesale electricity market for power plants that run on domestic coal.

It has strong political backing from Spain’s prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, who hails from Spain’s coal-mining region of Castilla y Leon.

The Spanish government has tried to justify the plan on “security of supply” grounds, arguing that there is a risk that indigenous coal plants could close, leaving supplies vulnerable when economic recovery kicks in.

Adding to tensions, miners at two companies in the north have threatened industrial action this week over unpaid wages, after staging road blocks, sit-ins and other protests during the past few weeks.

Spanish officials have latched on to a clause in the EU energy directive that allows a member state to give priority to the output from power plants using indigenous fuel, subject to a 15 per cent cap, “for reasons of security of supply”.

But the plan, which needs approval from competition authorities in Brussels because of the state aid element, is heavily opposed by domestic power producers and environmentalists alike, and has also been criticised by Spain’s domestic energy regulator and competition authority.

If anything, the European Commission's crackdown on coal-production subsidies is long overdue. Until now, Brussels has spared coal mining in its long-running war against industrial subsidies thanks to the miners' political clout, and so politicians have been able to keep high-cost and low-quality production alive on public life-support. In Spain, that amounts to an estimated €1 billion per year total being shoveled into the industry. Given this public largesse, it's hardly surprising that the EU's order could endanger the livelihoods of the country's 8,000 coal workers, and up to 40,000 jobs in peripheral sectors. Spanish coal workers have never had to conform to market demands before, so being forced to now may well be an existential threat to the entire industry.While it seems hard to imagine that the EU will decide to extend the subsidies, both the FT and WSJ see it as a possible outcome. Whatever decision is reached, it will have far reaching implications for EU energy and climate policies, so it bears watching.

21 September 2010

Free Trade and Green Jobs

At the Climate Change Law Blog, Daniel Firger has an interesting post on an emerging dispute between Japan and Canada over subsidies for "green jobs." Firger explains:

In what may be an ominous shot across the bow for green jobs advocates, Japan on September 13 submitted a complaint to the World Trade Organization alleging that a Canadian renewable energy law violates WTO non-discrimination rules. [1] At issue are a set of domestic content requirements built into Ontario’s landmark green energy law, [2] which are designed to guarantee that local producers – and local jobs –supply a minimum percentage of the technology used to meet the province’s ambitious goals for renewable energy generation. [3] While Japan’s “Request for Consultation” with Canada does not formally initiate a case before the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), it nevertheless sets the stage for a high-stakes showdown between the two countries, with potentially global repercussions for energy and industrial policy linking renewable power to high tech employment opportunities.What does this mean for the US? Firger says that is not yet clear. What is clear that efforts to prop up industries using government subsidies are unlikely to go unnoticed in our globalized world.

Seeing the Light

At the Albuquerque Journal, John Fleck has an excellent piece on technological advances in lighting technology and Jevons Paradox. Here is an excerpt:

That is right. Fleck explains:

Jeff Tsao's 1999 white paper on the case for next-generation, super-efficient light bulbs makes a point so obvious that it seems to require no explanation.What is this? Advances in efficiency might presage greater energy consumption?!

A solid-state light bulb that uses half the electricity of conventional bulbs would cut lighting-related energy consumption in half, right?

"The worldwide amount of electricity consumed by lighting would decrease by more than 50 percent," the Sandia Labs researcher and his colleagues wrote, "and total worldwide consumption of electricity would decrease by more than 10 percent."

A decade later, Tsao's thinking has evolved.

In a new paper, a team led by Tsao has drawn international attention by arguing that, instead of leading to reduced energy consumption, super-efficient bulbs may instead lead to people simply using more light.

That is right. Fleck explains:

To understand why, take a trip to the villages in rural Costa Rica where Michael Fark has been working.Here is how I described Jevons Paradox one year ago:

Fark heads a Canadian nonprofit called Lighting Up The World, which has been trying to get the super-efficient light bulbs developed by people like Tsao into the hands of the people who need them most.

There, one- or two-room clay brick houses are usually lit by candles or kerosene lamps.

It is lousy light by our standards, barely enough for the young Costa Ricans to do evening schoolwork after a day of helping in the fields. But that light, dim as it may be, is so precious that families spend up to 30 percent of their cash flow on candles or kerosene for a few hours of light per day, according to Fark.

Give the Costa Rican farm families a more efficient way to light their homes, as Fark's organization is doing, and they will choose to consume more light, not less energy.