A first step is to define what I mean by “innovation.” Economics in the Schumpeterian tradition defines innovation as one component of the so-called “linear model of innovation” (see Godin, here in PDF) which lays out technological change as a process of

Invention ---> Innovation ---> DiffusionMuch has been written about this model (PDF), which I will review at another time. However it has been used in the economic literature over the past half-century, Schumpeter himself defined innovation very precisely (and did not follow the so0called linear model):

. . . any “doing things differently” in the realm of economic life - all these are instances of what we shall refer to by the term Innovation. It should be noticed at once that that concept not synonymous with “invention”. . . It is entirely immaterial whether an innovation implies scientific novelty or not. Although most innovations can be traced to some conquest in realm of either theoretical or practical knowledge, there are many which cannot. Innovation is possible without anything we should identify as invention and invention does not necessarily induce innovation, but produces of itself no economically relevant effect at all. . .In a nutshell:

We will now define innovation more rigorously by means of the production function previously introduced. This function describes the way in which quantity of product [outputs] varies if quantities of factors [inputs] vary. If, instead of quantities of factors, we vary the form of the function, we have an innovation. ... We will simply define innovation as the setting up of a new production function. This covers the case of a new commodity, as well as those of a new form of organization. ... Innovation combines factors in a new way.I will return to the technical aspects of the so-called “production function” (illustrated below) in a later post. For now, it is only important to understand that an innovation changes the relationship between inputs and outputs in the economy. For instance, a restaurant takes employees (labor), food, appliances (and other capital) and combines them to make meals. A change in the relationship between the various inputs and meals served would be an innovation, which would be measured by a change in the rate of productivity.

What Schumpeter called “innovation” seems to have been characterized as “technology” by many economists in the years since. For instance, Daron Acemoglu in his widely read textbook on economic growth explains:

Economists normally use the shorthand expression “technology” to capture factors other than physical and human capital that affect economic growth and performance. It is therefore important to remember that variations in technology across countries include not only differences in production techniques and in the quality of machines used in production but also disparities in productive efficiency.Which of course brings us to Hooters girls, the hot young women in skimpy clothes who serve chicken wings and other delicacies at the US restaurant chain called Hooters. The company explains its innovative approach to the restaurant business as follows:

The first Hooters opened October 4, 1983, in Clearwater, Florida. During its history, the Hooters concept has undergone very little change. The current logo, uniform, menu and ambiance are all very similar to what existed in the original store. This lack of change is understandable given the tremendous success the Hooters concept has enjoyed. Hooters has continued to rank high amongst the industry's growth leaders. Hooters has proven successful in small-town America, major metropolitan areas and internationally. . .The company explains its name and innovative approach:

The element of female sex appeal is prevalent in the restaurants, and the company believes the Hooters Girl is as socially acceptable as a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader, Sports Illustrated swimsuit model, or a Radio City Rockette. The Hooters system employs over 25,000 people - over 17,000 of which are Hooters Girls. The "nearly world famous" Hooters Girls are the cornerstone of the Hooters concept, and as part of their job, these all-American cheerleaders make promotional and charitable appearances in their respective communities. Hooters hires women who best fit the image of a Hooters Girl to work in this capacity. The chain hires both males and females to work in management and host, staff, service bar, and kitchen positions. The Hooters Girl uniform consists of orange shorts and a white tank top. Pantyhose and bras are required.

The chain acknowledges that many consider "Hooters" a slang term for a portion of the female anatomy. Hooters does have an owl inside its logo and uses an owl theme sufficiently to allow debate to occur over the meaning's intent. The chain enjoys and benefits from this debate. In the end, we hope Hooters means a great place to eat. . .So what Hooters has done, in Schumpeterian innovation terms, is to combine input factors in a new way. In this case the company has carefully selected its labor in a precise manner intended to increase the demand for its product. Presumably, the underlying assumption is that a different labor pool would result in a lower demand. So while all of the other inputs (food, appliances, etc.) could have remained the same as any other restaurant chain, the Hooters innovation led to a restaurant chain that (they claim) “has continued to rank high amongst the industry's growth leaders.”

Sex appeal is legal and it sells. Newspapers, magazines, daytime talk shows, and local television affiliates consistently emphasize a variety of sexual topics to boost sales. Hooters marketing, emphasizing the Hooters Girl and her sex appeal, along with its commitment to quality operations continues to build and contributes to the chain's success. Hooters' business motto sums it up, "You can sell the sizzle, but you have to deliver the steak.”

The discipline of economics does have a terminology for the type of innovation represented by the Hooters girl – “technical change that is Hicks biased.” What "Hicks biased" technical change means is that unlike – say -- a new chicken wing fryer that can produce more wings per employee, but otherwise leaves labor and capital unchanged, some changes in the input-output relationship that result from "technology" are not independent of labor or capital (an example of the latter would be the substitution of low-sulfur Wyoming coal for West Virginia coal to reduce air pollution, but I digress).

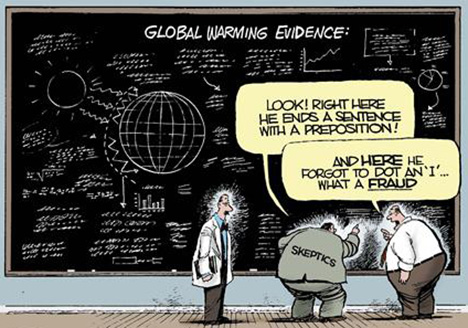

It is of course hard to think of the Hooters girls as any sort of "biased technical change to the production function," and the tortured language begins to shed some light on the limits of economics in the context of Schumpeterian innovation.

Economics does well in providing a framework for understanding the effects on productivity of innovations that result from new chick-wing fryers, but runs into troubles in providing a framework for understanding Hooters girls as innovations. This I think, helps to explain why economics has focused on “technology” rather than “innovation” (in the original Schumpeterian sense). Make no mistake, economics is critically important, but to understand innovation -- how it happens, and crucially, how it is directed and regulated -- requires more than what economics can offer.