As it turns out, nothing very good. I'll explain why in a second, but first of all, there's something you need to know about Canada. Americans like to picture Canada as a progressive, friendly, extremely green and Kyoto Protocol-signing sort of country—and in many ways it is. But the truth is, Canada is also a petrostate. The country has 175.2 billion barrels of oil in reserves, third-most in the world, and it produces 2.6 million barrels of crude oil a day. When we think of foreign oil in the U.S., most of us imagine a Saudi sheik or a Venezuelan despot, but the single biggest supplier of foreign oil to the U.S. is our friendly neighbor to the north. And thanks to the growth of oil sands (or tar sands, depending on how polluting you consider them), petroleum and fossil fuel energy in general has only become more important to the Canadian economy, moving the country's power center to the West, where politicians like Harper hail from.

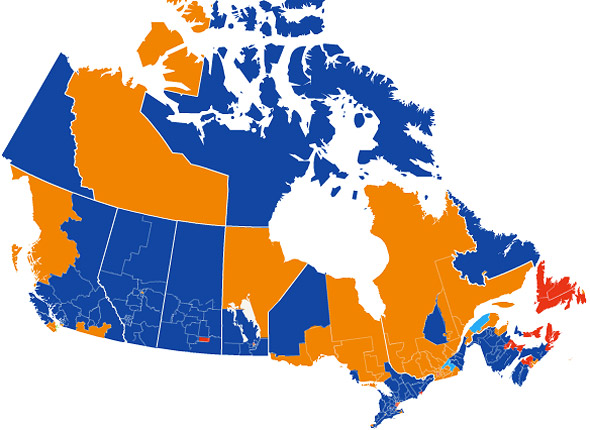

So Harper's clear victory means you can expect more industry-friendly policies from the now ruling Conservative Party, which is a little bit like Republicans-lite. That also means that Canada will continue its antagonism on the global climate stage, where it has long since abandoned any possibility of meeting its Kyoto carbon reduction targets, not that it was going to happen anyway. (Harper, back in a 2002 letter, referred to the Kyoto Protocol as a "socialist scheme.") Like his ideological counterpart George W. Bush, Harper doesn't seem to have much interest in dealing with climate change or energy, aside from the oil and gas that has helped Canada thrive recently. His position was in stark opposition to the opposition NDP, which offered more support for clean energy and—importantly—was ready to offer a carbon cap-and-trade program. But the Conservatives argued—in very familiar language—that carbon pricing would be increase energy prices and be a drag on the economy. Last night—in a possible example of what Roger Pielke Jr.'s "iron law of climate policy"—the Conservatives won, meaning that for now, carbon pricing in Canada is even less likely than it will be in the U.S.

It wasn't all bad—the fact that the Green Party now has a member in parliament puts Canada ahead of the U.S., while the NDP has proven to be a stronger green party on its own than the Liberals ever were. Harper's Conservatives may have a majority in Parliament, but they won less than 40% of the vote by number, meaning that public opinion on climate and the environment may be significantly more divided than the results suggest. And like in America, climate change and energy policy doesn't appear to have been a major issue for most voters. But there's no getting around the fact, as University of British Columbia political scientist George Hoberg blogged today:

The 2011 Canadian election is very bad news for the climate movement.

03 May 2011

What Does Canada's Election Mean for Climate Policy?

In case you missed it, Canada just had an historic election. Bryan Walsh asks, what it might mean for climate policy? He gives this answer: