The first article discusses Google' Goggles which is an application allows people to search the internet based on an image taken by a smartphone. Google has decided not to allow this technology to include face recognition in its software, even though people have requested it.

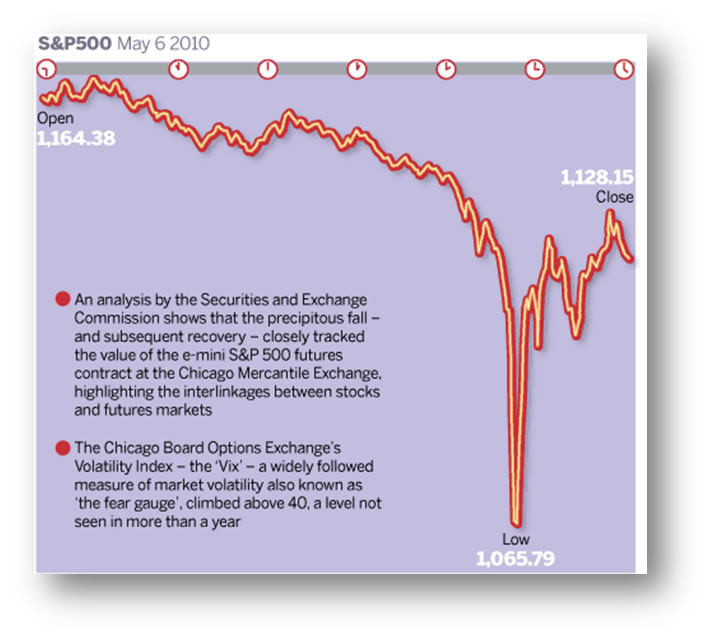

“With every technology, there is a dark side,” said Hany Farid, a computer scientist at Dartmouth. “Sometimes you can predict it, but often you can’t.”The second article focuses on innovations in high frequency trading in financial markets, which bears some responsibility for the so-called "flash crash" of May 6th last year, in which the DJIA plunged more than 700 points in just minutes.

A decade ago, he noted, no one predicted that cellphones and text messaging would lead to traffic accidents caused by distracted drivers. And, he said, it was difficult to foresee that the rise of Facebook and Twitter and personal blogs would become troves of data to be collected and exploited in tracking people’s online behavior.

Often, a technology that is benign in one setting can cause harm in a different context. Google confronted that problem this year with its face-recognition software. In its Picasa photo-storing and sharing service, face recognition helps people find and organize pictures of family and friends.

But the company took a different approach with Goggles, which lets a person snap a photograph with a smartphone, setting off an Internet search. Take a picture of the Eiffel Tower and links to Web pages with background information and articles about it appear on the phone’s screen. Take a picture of a wine bottle and up come links to reviews of that vintage.

Google could have put face recognition into the Goggles application; indeed, many users have asked for it. But Google decided against it because smartphones can be used to take pictures of individuals without their knowledge, and a face match could retrieve all kinds of personal information — name, occupation, address, workplace.

“It was just too sensitive, and we didn’t want to go there,” said Eric E. Schmidt, the chief executive of Google. “You want to avoid enabling stalker behavior.”

The episode seemed to demonstrate the vulnerabilities of the new market, and just what could happen when no humans are in charge to correct the machines.The world is in a era of continuous technological change, prompting some to ask for it to slow down:

Since the flash crash, the S.E.C. and the exchanges have introduced marketwide circuit breakers on individual stocks to halt trading if a price falls 10 percent within a five-minute period.

But some analysts fear that some aspects of the flash crash may portend dangers greater than mere mechanical failure. They say some wild swings in prices may suggest that a small group of high-frequency traders could manipulate the market. Since May, there have been regular mini-flash crashes in individual stocks for which, some say, there are still no satisfactory explanations. Some experts say these drops in individual stocks could herald a future cataclysm.

In a speech last month, Bart Chilton, a member of the futures trading commission, raised concerns about the effect of high-frequency trading on the markets. “With the advent of ‘Star Trek’-like, gee-whiz H.F.T. technology, we are witnessing one of the most game-changing and tumultuous shifts we have ever seen in financial markets,” Mr. Chilton said. “We also have to think about the myriad ramifications of technology.”

One debate has focused on whether some traders are firing off fake orders thousands of times a second to slow down exchanges and mislead others. Michael Durbin, who helped build high-frequency trading systems for companies like Citadel and is the author of the book “All About High-Frequency Trading,” says that most of the industry is legitimate and benefits investors. But, he says, the rules need to be strengthened to curb some disturbing practices.

“Markets are there for capital formation and long-term investment, not for gaming,” he says.

But some analysts question whether everyone benefits from this technological upending.The metaphor leaves unanswered who it is that installs those lights and the manner through which we might arrive at collective decisions about innovation in pursuit of shared societal outcomes.

“It is a technological arms race in financial markets and the regulators are a bit caught unaware of how quickly the technology has evolved,” says Andrew Lo, director of the Laboratory for Financial Engineering at M.I.T. “Sometimes, too much technology without the ability to manage it effectively can yield some unintended consequences. We need to ask the hard questions about how much of this do we really need. It is the Wild, Wild West in trading.”

Mr. Lo suggests a need for a civilizing influence. “Finally,” he says, “it gets to the point where we have a massive traffic jam and we need to install traffic lights.”

As the case of face recognition in Google's Goggles might suggest, the pace of deployment of certain innovations can be slowed, for a while at least, in the absence of regulatory action. But I wouldn't be surprised to learn that facial recognition capabilities are already or soon will be available. If it were to be deployed in certain settings, such as in US airports as a form of security check or in the UK as an add-on to CCTV technology, we can surely expect a broader public debate.

The case of high frequency trading indicates that governments and companies can work together to regulate the use of technology in ways that are judged democratically legitimate and procedurally fair. It also indicates a common tendency to deploy innovations first and deal with the consequences later. Where those consequences are unintended and unexpected, we may have no other choice.

This situation raises what I see to be core questions in the governance of innovation -- to what degree can innovation be shaped for achieving intended purposes? and, To what degree can the consequences of innovation be anticipated?

On this blog, the coming year will see much more attention to these questions.