Global warming is dangerously overheated.

There is no escape from the shouting. However meticulous the science, prediction is only prediction. As Ian McEwan recently reminded us in his novel Solar, climate science is as riven by ego, jealousy, mixed motives and exaggeration as any other branch of human thought. The range of possible outcomes seems confusingly wide.To the bemused onlooker, it seems to be a branch of predictive science dominated by empurpled men bellowing at one another. Self-righteous doomsters lick their lips as they list the horrors rushing towards us as a direct result of our greed and selfishness. Self-righteous “sceptics” pounce on mistakes by scientists to denounce the whole man-made global warming thesis as a leftish, hairshirt-wearers’ plot.

31 May 2010

Andrew Marr Summarizes the Climate Debate in Two Paragraphs

28 May 2010

Misrepresentation of the IPCC CO2 Emission Scenarios

In a correspondence in Nature Geoscience a group of scholars (Manning et al. 2010) take issue with claims made by the Global Carbon Project that has fed into oft-repeated claims that global emissions are increasing above the highest of IPCC scenarios. For instance, in 2008 the GCP issued a press release that claimed:

In a correspondence in Nature Geoscience a group of scholars (Manning et al. 2010) take issue with claims made by the Global Carbon Project that has fed into oft-repeated claims that global emissions are increasing above the highest of IPCC scenarios. For instance, in 2008 the GCP issued a press release that claimed:Emissions growth for 2000-2007 was above even the most fossil fuel intensive scenario of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (SRES-IPCC).This perspective has been echoed by activists, such as Joe Romm, who wrote the following in Nature Reports Climate Change:

Carbon emissions from the global consumption of fossil fuels are currently above 8 GtC per year and rising faster than the most pessimistic economic model considered by the IPCCThe problem with such statements is that they are wrong. (To defend GCP a bit, their presentation has become a bit more nuanced in more recent years, but still not quite correct.) Manning et al. explain the problem that they seek to correct:

Fossil fuel CO2 emissions have increased significantly. However, contrary to some statements in recent publications1–3, current emissions are not higher than covered in the climate change scenarios used by the last two Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments4,5. And although emissions were recently near the top of the range that has been covered6, the changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration follow long-term average emissions rather than short-term variations.The problem lies in a technical distinction between scenario averages (the mean across a family of scenarios) and scenario markers (a representative scenario from a family). Manning et al. expalin:

We therefore take issue with the comparison8,9 of the estimated evolution of industrial CO2 emissions since 1990 with subgroup averages of the SRES scenarios, rather than with the illustrative scenarios. These comparisons can be misleading over the next few decades because the upper boundary of the range covered by subgroup average emissions is significantly lower than the upper boundary of the range of illustrative scenarios. As a result, the comparisons with subgroup averages have led others1–3,10 to incorrectly conclude that current emissions are higher than the values used in climate change projections. This may be spreading into general reviews of climate change science11,12, causing a growing inconsistency between the modelling work that has been done for the IPCC and its broader interpretation.The figure at the top of this post is from the Manning et al. paper.

Interestingly, I wrote an email to the GCP in November, 2007 as part of a discussion on this exact issue, making essentially the same points. Here are some excerpts from what I sent to GCP:

The IPCC SRES has 40 scenarios from four "families" of emissions. The emissions profiles for fossil fuel and industry for these 40 are provided here:The fact that emissions have been running at the top half of the SRES range, and above most of the marker scenarios is troubling enough, for reasons that we explained in Nature in 2008 (Pielke et al. 2008, PDF). There is no need to misrepresent the science to claim that things are worse than we thought. The are already worse than we thought without the misrepresentation.

http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc/emission/5-2.htm

Looking across the 40 SRES scenario projections for 2010 fossil fuel and industry CO2 emissions shows a range of 7.25 to 10.32 GtC, equating to annual growth rates of .05% to 3.95% per year. If the 2000-2006 observed growth rate is 3.3% per year wouldn't this suggest that figure 7 in the November 15 GCP_CarbonCycleUpdate is fairly misleading, and in fact incorrect when it states:"Current emissions are tracking above the most intense fossil fuel emission scenario established by the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios-SRES (2000)"?For its part the IPCC SRES report notes, "The wide ranges of energy and industry-related CO2 emissions in the SRES scenarios reflect the fact that the "best" or the "most likely" quantifications are nearly impossible to identify." Would it not be accurate to say instead that current emissions remain within the envelope of estimates provided by the IPCC in 2000, but in the top 12.5% of scenarios (there are 5 of 40 at a growth rate of 3.3%/year and higher for 2000-2010)? . . .

I think that taking either the marker or the average of the SRES scenario families is far less robust than simply presenting the envelope of projections in the entire 40 scenarios. The IPCC itself urges great caution in aggregating scenarios, and goes to great length to advise that there is no basis for assign probabilities to any of them (hence, no basis for averaging).

So I would urge some greater caution in how you present the recent trends than I observe in your powerpoint. They are surprising and very significant, but they are not outside the IPCC SRES envelope (though perhaps outside your own simpliifcation of that envelope). Your message is far too important to risk being caught up in such a silly point.

Kudos to Manning et al. for helping to set the record straight.

Offshore Drilling Realities

Earlier this week, Senator John Kerry (D-MA) dresses down someone (who, I wonder?) for apparently showing a lack of understanding of the realities of oil exploration in the Gulf of Mexico:

Earlier this week, Senator John Kerry (D-MA) dresses down someone (who, I wonder?) for apparently showing a lack of understanding of the realities of oil exploration in the Gulf of Mexico:Now we are not going to stop drilling in the Gulf tomorrow, folks. Let’s be realistic. There are 48,000 wells out there. One of them went sour. About 30 percent of our transportation fuel comes from the Gulf. You think Americans are going to suddenly stop driving to work tomorrow? Do you think people are going to stop driving the trucks to deliver the goods to the department stores? Not going to happen.Today's FT Lex Column offers some additional realities:

It speaks to the perverse counter-intuitive nature of energy and climate policies that the best-intentioned actions -- strengthening US drilling regulations, could lead to greater environmental risks and do nothing to address carbon dioxide emissions. Policy design desperately needs to catch up with real-world complexities.US regulations could become so onerous that offshore activity dries up in North America, but this would boost the appeal of fields off West Africa, Brazil and in the Barents Sea. And, though it seems callous with crude still fouling the Gulf, keeping North American offshore drilling viable may pose less environmental risk than other options. Incremental barrels would come from abroad by tankers statistically more likely to spill, or from ecologically damaging oil sands, today’s marginal supplier.

The economic attractions of offshore drilling are just too compelling for the industry to be spooked even by BP’s debacle. Oilmen will go where the oil is, however painful their burns.

27 May 2010

UVA Tells Cuccinelli to Show His Cards

The University of Virgina has petitioned a court to set aside the request of Virginia Attorney General Kenneth Cuccinelli to Michael Mann, a former professor at UVA, for disclosure of a large amount of material related to his research while a faculty member by invoking a statute focused on rooting out fraud in the use of public funds.

The University of Virgina has petitioned a court to set aside the request of Virginia Attorney General Kenneth Cuccinelli to Michael Mann, a former professor at UVA, for disclosure of a large amount of material related to his research while a faculty member by invoking a statute focused on rooting out fraud in the use of public funds.The petition (here in PDF) basically calls Cuccinelli's bluff. I wrote about this earlier this month, arguing that "I'm no lawyer, but the chances of Mann being found guilty of violating this statute are precisely zero." The petition explains that Cuccinelli's request fails on both procedural and substantive grounds - the two Aces in the hole.

However, since this is a public relations stunt by the Attorney General, he could still win in the court of public opinion, even if the petition were to be granted on procedural grounds, by showing evidence of the fraudulent use of taxpayer money by Mann. On the other hand, if he cannot show such substance, he will be the one that looks like a fraud on a fishing expedition. As I wrote this month, I don't think that the AG has the evidence, because there is no such evidence to have.

What about Michael Mann and climate science? As I wrote earlier this month:

The worst that can be said about Mann is that he may have done sloppy research using poor methods that won't stand the test of time, and when challenged he tends to act petulant and nasty. Let's just accept this as true for the purposes of discussion. OK, so what? None of this rises to scientific misconduct or fraud, not even close, and no one has even made such a case, despite the ample noise in the blogosphere.If this plays out as I anticipate, with the petition granted and the AG coming up with nothing, then Mann and his supporters would do well not to confuse this legal victory with evidence for scientific accuracy and integrity -- a conflation that has been too often made in the aftermath of the recent UK reviews of the UEA situation, which simply adds to the partisan flames.

Mann's opponents will continue to shout "fraud" but until they can match the talk with evidence, they should probably stay silent. If Mann is confident that his files show no wrongdoing, he might consider just releasing them after the petition is granted as a gesture of his confidence. I doubt that would happen, but it would be quite powerful if it was done by choice, not by coercion.

However, after this episode is over, I expect fault lines to remain pretty much as they were before and the battle will simply shift to new turf in the never-ending climate wars.

The Significance of Climate Model Agreement: A Guest Post by Ryan Meyer

Ryan Meyer is a PhD student at ASU's School of Life Sciences where he is writing a dissertation about US federal climate science research and its relationship to policy making. He is spending a yer in Australia on a Fulbright and he blogs at Adapt Already.

If four out of five global climate models (GCMs) agree on a result, should we feel more confident about that result? Does agreement among models constitute increased certainty about the models’ basis in reality? My colleagues and I wondered about this a few years ago when we started noticing that many climate scientists seem to adopt this logic without any explanation or justification. They claim, for example, that we should be more worried about drought in the southwestern US because 18 out of 19 models predict a transition to a more arid climate over the next 50 years. Or they pick a subset of models to represent a particular process such as the Asian monsoon, and then point to agreement among those models as significant.

If 18 models get the same result, is that better than just one? Why? Climate science should provide a thorough explanation for this, especially if climate models are to begin informing policy decisions.

We argue in a paper now available in Environmental Science and Policy (PDF here) that agreement is only significant if the models are sufficiently independent from one another. The climate science community has mostly ignored the crucial problem of model independence while taking advantage of a tacit belief in the force of model agreement. To quote from our introduction:

GCMs are commonly treated as independent from one another, when in fact there are many reasons to believe otherwise. The assumption of independence leads to increased confidence in the ‘‘robustness’’ of model results when multiple models agree. But GCM independence has not been evaluated by model builders and others in the climate science community. Until now the climate science literature has given only passing attention to this problem, and the field has not developed systematic approaches for assessing model independence.To some these arguments may seem like nitpicking. Or they might seem better suited to the pages of some technical journal where modelers work these things out for themselves. But we strongly believe that this extends beyond methodology, and is in fact a policy question. It relates to the kind of investments we can and should be making in climate science.

The question of independence is one small piece of a much needed broad discussion about climate science policy. What kinds of knowledge are most helpful in crafting a response to climate change? What institutions, disciplines, and tools are best suited to deliver such knowledge? Such crucial questions of science policy tend to be ignored. We argue about what "the science" says, rather than how it works and how it could work better for the needs of decision makers.

In our paper, we take it as a given that governments will continue to fund large and complex models of the climate and related systems. (A broader discussion about the merits of this investment is important, but we do not directly address it). But how should they be funded? Who should decide the most important questions to pursue? In the past, we have tended to let climate scientists sort that one out. They are, after all, the experts. But they are certainly not unbiased participants in this discussion. Are they asking the most important questions, or just the ones they find most interesting?

It is important to recognize that there are many possible trajectories for our climate science knowledge. We may not know exactly where each one leads, but we can still make wise, informed choices. This is why the independence problem is important, not just for climate modelers, but for science policy makers, potential users of climate science, and advocates for climate change adaptation.

We have three basic recommendations related to the independence problem:

- Climate modelers should be wary of overselling results based on model agreement.

- The climate science community should begin to better address the independence problem.

- Science policy decision makers should take this problem into account when building strategies for climate modeling, and climate science more broadly.

Political Realities

Yesterday, I discussed a proposal from the European Commission to increase the unilateral target for the bloc's emissions reductions to 30% from 20% by 2020. Since the proposal involves costs measured in the hundreds of billions of Euros (of which the exact amount seems to be reported differently), I argued yesterday that it is not going to happen.

Yesterday, I discussed a proposal from the European Commission to increase the unilateral target for the bloc's emissions reductions to 30% from 20% by 2020. Since the proposal involves costs measured in the hundreds of billions of Euros (of which the exact amount seems to be reported differently), I argued yesterday that it is not going to happen.EurActiv reports today that Connie Hedegaard, the EU's Climate Action Commissioner and person responsible for the proposal, has stepped back:

Are the conditions right now? Would it make sense at this moment? My answer would be 'no'These comments raise the question of when it would be appropriate to increase costs to European businesses. Certainly no time soon, maybe never.

The point here is not about Europeans specifically, who have certainly shown the most leadership on climate policies over recent decades, but about a general principle of policy design: People are willing to accept some costs for decarbonization policies, but this willingness has limits, even in Europe. In this regard, Europeans, North Americans, Asians and everyone else are much the same. This is an argument discussed in some depth in The Climate Fix. There is no point is complaining about this reality -- and little point in trying to change it -- rather, it needs to be accepted as a boundary condition for climate policy design.

26 May 2010

Don't Tread on Me

Team USA is set for the World Cup. Discussion here. One thing is for sure, come the end of June Bob Bradley will either be a coaching genius or unemployed.

Team USA is set for the World Cup. Discussion here. One thing is for sure, come the end of June Bob Bradley will either be a coaching genius or unemployed.U.S. 23-man World Cup roster

Goalkeepers

Tim Howard - Everton

Brad Guzan - Aston Villa

Marcus Hahnemann - Wolverhampton Wanderers

Defenders

Carlos Bocanegra - Rennes

Jonathan Spector - West Ham United

Oguchi Onyewu - AC Milan

Clarence Goodson - IK Start

Jay DeMerit - Watford

Steve Cherundolo - Hannover

Jonathan Bornstein - Chivas USA

Midfielders

Landon Donovan - Los Angeles Galaxy

Clint Dempsey - Fulham

Michael Bradley - Borussia Moenchengladbach

Ricardo Clark - Eintracht Frankfurt

Stuart Holden - Bolton Wanderers

Maurice Edu - Glasgow Rangers

Jose Francisco Torres - Pachuca

Benny Feilhaber - AGF Aarhus

DaMarcus Beasley - Glasgow Rangers

Forwards

Jozy Altiidore - Villarreal

Robbie Findley - Real Salt Lake

Edson Buddle - Los Angeles Galaxy

Herculez Gomez - Pachuca

Climate Policy Boundary Conditions

The Times reports that the European Union is set to propose increasing its unilateral emissions-reduction target to 30% by 2020:

The Times reports that the European Union is set to propose increasing its unilateral emissions-reduction target to 30% by 2020:The European Commission is determined to press ahead with the cuts despite the financial turmoil gripping the bloc, even though it would require Britain and other EU member states to impose far tougher financial penalties on their industries than are being considered by other large economies.

The plan, to cut emissions by 30 per cent on 1990 levels by 2020, would cost the EU an extra £33 billion a year by 2020, according to a draft of the Commission’s communication leaked to The Times.

What's that you just read?

"£33 billion a year by 2020"That is a total of about 400 billion Euros over 10 years. [UPDATE: A reader writes in to suggest that the Times has its currency wrong, the 33 billion should be in Euros. If so, then the total for the decade is 330 billion Euros. Thanks MW.] It is not going to happen. EurActiv reports the realpolitik:

France and Germany yesterday joined the growing ranks of European countries opposed to making further unilateral moves on climate change, as the European Commission today plans to make the case for raising the EU’s greenhouse gas reduction goal from -20% to -30% by 2020. . .For emissions reductions policies to succeed they simply cannot involve high costs (and yes, for the EU 400 billion Euros is a high cost). This is just a political reality, there is no point in complaining about it.The common declaration by France and Germany signals a hardening of Europe’s policy on climate change, six months after the failure of UN climate talks in Copenhagen.

It also deals a blow to Connie Hedegaard, the EU’s climate action Commissioner, who is expected to recommend today (26 May) that Europe raises its greenhouse gas reduction target from -20% to -30% by 2020.

25 May 2010

Incoherent Policy Narratives and Climate Skepticism

One of the enduring myths in the debate about climate change is that action to decarbonize economic activity depends upon a specific view of climate science. The logic holds that if people are concerned enough about climate change -- if they have sufficient alarm -- they will then have the motivation needed to support policies that have high costs and involve sacrifice. From this perspective, public opinion on climate science thus serves as a proxy for public support for policy action.

One of the enduring myths in the debate about climate change is that action to decarbonize economic activity depends upon a specific view of climate science. The logic holds that if people are concerned enough about climate change -- if they have sufficient alarm -- they will then have the motivation needed to support policies that have high costs and involve sacrifice. From this perspective, public opinion on climate science thus serves as a proxy for public support for policy action.This logic is flawed, both conceptually and empirically, as I'll illustrate by discussing a well-meaning but ultimately incoherent article on the front page of today's New York Times. The article explains how climate skepticism is on the rise in Great Britain.

Nowhere has this shift in public opinion been more striking than in Britain, where climate change was until this year such a popular priority that in 2008 Parliament enshrined targets for emissions cuts as national law. But since then, the country has evolved into a home base for a thriving group of climate skeptics who have dominated news reports in recent months, apparently convincing many that the threat of warming is vastly exaggerated.The article explains that the rise of skepticism threatens climate policies:

Politicians and activists say such attitudes will make it harder to pass legislation like a fuel tax increase and to persuade people to make sacrifices to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. . .The logic is flawed conceptually because "fervor about climate change" is far from the only reason that people support energy policies that advance decarbonization. Other reasons for public support include energy security, diversification, economic growth and jobs, replacing dirty energy with clean energy, energy reliability, costs and so on.

The lack of fervor about climate change is also true of the United States, where action on climate and emissions reduction is still very much a work in progress, and concern about global warming was never as strong as in Europe.

That the logic is flawed can be convincingly shown empirically. Consider that climate skepticism in Great Britain has been deemed to be a problem for years. For instance:

2007: "The public are far more sceptical about global warming than most politicians would have us believe, a new poll has revealed today."Yet, right in the middle of this period the UK government passed the 2008 Climate Change Act with essentially no opposition and broad public support. The Act mandates emissions reductions of 34% by 2020 and 80% by 2050, making it the most aggressive piece of national legislation anywhere. Skepticism about climate science presented no obstacle to passing this legislation.

2008: "Surprising politicians, a poll released Sunday indicates a majority of the British public does not believe human activity has caused global warming."

2009: "The British public has become more sceptical about climate change over the last five years, according to a survey."

The NYT also reports that more Americans believe that climate science has been exaggerated in public discussions:

A March Gallup poll found that 48 percent of Americans believed that the seriousness of global warming was “generally exaggerated,” up from 41 percent a year ago.Here is a hypothesis to consider: The public is smarter than they are often given credit for. It is possible that the public can at the same time support policies that lead to decarbonization of the economy while at the same time believing that climate science has been exaggerated.

The message from the public that many experts (including the media) have yet to comprehend is that policies which require "sacrifice" are nonstarters. It does not matter what the public believes about climate science, they are not (in general) going to sacrifice or endure hardship. This reality should be a boundary condition for policy design. With this consideration, the public has consistently supported action on climate change, notably moving to a less carbon-intensive economy. The policy challenge is thus to figure out how to design policies that meet these political realities, a challenge that policy experts have yet to tackle.

The NYT actually further politicizes climate science by implying that the battle over the integrity of climate science is one-and-the-same as the battle over climate policies:

Scientists have meanwhile awakened to the public’s misgivings and are increasingly fighting back. . . It is unclear whether such actions are enough to win back a segment of the public that has eagerly consumed a series of revelations that were published prominently in right-leaning newspapers like The Times of London and The Telegraph and then repeated around the world. . .By equating issues of science with issues of politics the NYT thus is apparently willing to minimize the issues of scientific integrity that have surfaced regarding the IPCC:

This narrative thus reinforces two sorts of policy failures:In January, for example, The Times chastised the United Nations climate panel for an errant and unsupported projection that glaciers in the Himalayas could disappear by 2035. The United Nations ultimately apologized for including the estimate, which was mentioned in passing within a 3,000-page report in 2007.

Then came articles contending that the 2007 report was inaccurate on a host of other issues, including African drought, the portion of the Netherlands below sea level, and the economic impact of severe storms. Officials from the climate panel said the articles’ claims either were false or reflected minor errors like faulty citations that in no way diluted the evidence that climate change is real and caused by human activity.

First, it perpetuates a flawed expectation that once people only believe enough or the right things, they will then be willing to make sacrifices leading to successful climate policies. Yet, public opinion on this point has been constant for decades -- support for decarbonization policies is not about belief in science, but rather the short-term costs and benefits of proposed policy action, which has nothing to do with long-term climate change. Similarly, that the public does not want sacrifice has been a constant in public opinion.

Second, it enables the pathological politicization of science not just by equating views on science with views on policy, but also by encouraging the looking past real problems in the IPCC. The logic of this narrative holds that if climate science is in any way diminished, then support for action is necessarily reduced, so it is best to look away from problems in science, or even to minimize them. The public is no so easily fooled. However, looking at actual poll data should be enough to show that views on climate science are not tightly correlated with support for action on energy policies that accelerate decarbonization.

The NYT concludes:

The public is left to struggle with the salvos between the two sides.The public is in fact doing just fine. It is the media and other elites who continue to carry along an incoherent narrative who are doing most of the struggling. When they start listening to what the public is actually saying, rather than trying to force public opinions into a predefined but ultimately unrealistic mold, might be the time when debate over climate policy truly opens up.

You can read a more in depth treatment of this argument in my forthcoming book, The Climate Fix: What Scientists and Politicians Won't Tell You About Global Warming. Pre-order your copy today ;-)

Warnings by Mike Smith

I first met Mike Smith in 1997 at a workshop at NCAR that I organized on the societal impacts of weather in the United States. Mike had the energy and enthusiasm of a human tornado, and has impressed me immeasurably ever since. I had the pleasure of serving on his board of directors in the early 2000s, where I learned an enormous amount about the role of weather in business, as well as the business of weather. We've remained friends and colleagues since that time. Mike is a first rate scientist, entrepreneur and now, author.

I first met Mike Smith in 1997 at a workshop at NCAR that I organized on the societal impacts of weather in the United States. Mike had the energy and enthusiasm of a human tornado, and has impressed me immeasurably ever since. I had the pleasure of serving on his board of directors in the early 2000s, where I learned an enormous amount about the role of weather in business, as well as the business of weather. We've remained friends and colleagues since that time. Mike is a first rate scientist, entrepreneur and now, author.Given Mike's past successes, it is no surprise that his first book, Warnings: The True Story of How Science Tamed the Weather is a fascinating and fun read. Mike was the first person to ever take a picture of a "downburst," helping to settle an intense debate in the meteorological community over whether these phenomena actually existed and were responsible for a number of deadly jet crashes in the 1960s through 1980s. He describes this little-known (outside of meteorological circles) debate and its consequences, making for a fascinating history. Mike also explores the history and evolution of tornado warnings in the United States, describing the complicated and sometimes contested relations between public agencies, the media and the private sector. The book describes the real world impacts of tornadoes, and the efforts of scientists to protect life and property.

If you are interested in gripping and educational story about science, I strongly suggest adding Warnings to your summer reading list. It is a lot of fun, and written by someone who has participated in the evolution of modern meteorology as a participant with a front row seat, both to the weather and our efforts to tame it.

Mike blogs at Meteorological Musings. What a great book, Congrats Mike!

Defying Joe Romm

In characteristic fashion, fierce climate blogger Joe Romm excoriates the authors of a recent paper in Nature on malaria and climate change for writing the following in their paper:

In characteristic fashion, fierce climate blogger Joe Romm excoriates the authors of a recent paper in Nature on malaria and climate change for writing the following in their paper:. . . model predictions, reported widely in global climate policy debates3, 6, 7, [suggest] that climate change is adding to the present-day burden of malaria and will increase both the future range and intensity of the disease.Footnote 6 goes to IPCC WGII 2007 (footnote 3 goes to the dodgy McMichael et al., study which argues that climate change has already lead to an increase in malaria deaths). Romm argues that the IPCC WGII cannot be used to support the claim made in the paper about model studies showing an increase in malaria burden worldwide. Joe defies anyone show that he is wrong.

I defy anybody to read the relevant sections, which I excerpt at length here, or search WGII for every single use of the word “malaria,” and see how it could possibly be used to support the sentence in the Nature piece where it appears. It cannot. Quite the reverse, in fact. And it certainly is not a high profile prediction of a current and future worsening of the disease in a warmer climate. Quite the reverse.Well, Joe, if I must show that you are completely wrong . . . If you look at the IPCC WGII TS (PDF, p. 47), it clearly says that model studies show an increase in the global burden of malaria (emphasis added):

Mixed projections for malaria are foreseen: globally an estimated additional population at risk between 220 million (A1FI) and 400 million (A2) has been estimated. In Africa, estimates differ from a reduction in transmission in south-east Africa in 2020 and decreases around the Sahel and south-central Africa in 2080, with localised increases in the highlands, to a 16-28% increase in person-months of exposure in 2100 across all scenarios. For the UK, Australia, India and Portugal, some increased risk has been estimated.This statement is utterly unambiguous and contradicts Joe's claim that the IPCC did not project a future with an increased malaria burden due to climate change. The Nature paper was properly cited.

Why then is Joe huffing and puffing? Perhaps it is because he has been among those hyping a malaria-climate change link, referencing it often on his blog. Consider that it was just one year ago that Romm was criticizing the IPCC for low-balling its projections of climate impacts, approvingly repeating that:

Climate change will have devastating consequences for human health . . . Malaria, tick-borne encephalitis, and dengue fever will become increasingly widespread.Other experts are starting to get tired of Romm's antics, such as David Stern at ANU:

Some of my coauthors on our work on malaria and climate change have an article (with others) in the latest issue of Nature. Their main point is that even if climate change has had an effect on the prevalence of malaria in the last century, that effect is swamped by everything else that has been going on. Also that the current distribution of malaria endemicity is no guide to future trends. Both these points seem pretty sensible to me but Joe Romm is outraged. He describes the authors of the paper as "sloppy" because he thinks they exaggerate the degree to which the IPCC support the "Malaria is increasing due to climate change hypothesis". This is a rather indirect criticism. He thinks the IPCC underplayed the threat and accuses them of saying the IPCC overplayed the threat. That's the best he's got against their paper... It's typical of Romm to trash a paper for extraneous reasons if it doesn't fit the global warming is always bad everywhere party line.And also David Smith, a co-author on the Nature paper,

Joe Romm never contacted any of the authors of our study, but he does make some angry accusations. For the record, I’ve read the IPCC report, including the relevant sections. I’m part of the consensus that believes the world is warming and that human activities are the main cause.[UPDATE: David Smith returns to DotEarth with another comment, here is an excerpt:

Joe Romm picked one sentence and one reference from our Nature paper and twisted it into a controversy. Then, he wrote a second, very aggressive post about my “non-response” posted here, in which he argues that I’ve tacitly confirmed the overblown controversy he’s stoked up. I've decided in advance not to read or respond to any more of Joe Romm's blogs after this, even if they're all about me. . .]

On the whole, the academic publications about climate and malaria are a perfect example of hype. Peer reviewed publications on warming and malaraia have almost universally argued that warming will increase the burden and extend future range of malaria. Paul Reiter has been an outstanding spokesman for the other point of view. . .

The way Romm has framed this particular controversy, he wants to make us look bad no matter what we say or don’t say. That’s the whole point of being so aggressive with his “righteous anger.” I feel like the politician who was asked when he had stopped beating his wife. So how do I do the equivalent of answering, “I’m not married.”

I’m impressed at the way Joe Romm has taken that one sentence and its citation and made two complete blog posts out of it.

I wonder if "I wuz wrong" and "I'm sorry" are in the vocabulary of the fiercest climate blogger?

24 May 2010

World Cup vs. Champions League: Mourinho's Hypotheiss

In the lead up to the Champion's League final, Jose Mourinho said:

In the lead up to the Champion's League final, Jose Mourinho said:"This game is the most important in the world. It is even bigger than the World Cup because the teams in it are at a higher level than national teams, who can't buy the best players."We can forgive the Special One for a bit of hyperbole, but his comments raise an interesting hypothesis that can in fact be addressed empirically.

FutebolFinance.com provides a ranking of the transfer value of the top teams in the World Cup, as of late 2009, as follows:

The 10 most valuable teams in the world 2009Where would Inter Milan and Bayern Munich appear on this list? I have been unable to find a similar list for club teams. However, we can hazard a guess based on some relevant overall team value information. We can compare this to a more-or-less contemporary assessment of the player value of the Champions League entrants for the Premier League, courtesy of The Daily Mail:

- Spain - 565 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 2nd place)

- Brazil - 515 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 1st place)

- France - 450 million Euro (10th in FIFA Ranking)

- England - 440 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 7th place)

- Italy - 400 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 4th place)

- Argentina - 390 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 8th place)

- Portugal - 340 million Euros (17th in FIFA Ranking)

- Germany - 305 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 4th place)

- Netherlands - 280 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 3rd place)

- Russia - 210 million Euros (FIFA Ranking 6th place)

1. Chelsea - 232 million EurosAn important qualification is that The Daily Mail valuations are what the teams cost to assemble not what the players are actually worth in the transfer market. The transfer market is illiquid and not all data on transfers is readily available (or if it is I have yet to find it). For instance, with reports today that Fabregas is worth some 40 million Euros, and Arsenal's reliance on players from within the club, the team valuation was probably low. So let's just double the valuation for the EPL Champions league participants to address this uncertainty. Even so, only Chelsea would crack the value of the top 3 national teams and Arsenal would not make the top 10.

2. Manchester United - 220 million Euros

3. Liverpool - 163 million Euros

4. Arsenal - 86 million Euros

The conclusion that I reach is that -- for at least the knock-out stages of 16 teams -- the Champions League is full of great players, but that the World Cup remains supreme, at least as measured by the economic value of players on teams.

Mourinho's hypothesis does not hold up.

Boulder Transportation Trend Study

Today's Daily Camera has an incomplete article about a recent study (PDF) about Boulder's transportation trends in relation to policy goals. The article reports:

Today's Daily Camera has an incomplete article about a recent study (PDF) about Boulder's transportation trends in relation to policy goals. The article reports:Boulder residents continue to drive less and ride bicycles and walk more compared to the national average, according to the city's latest "Mode Shifts" study.

But the trend still isn't on track to meet the city's goal of reducing traffic to 1994 levels by 2025.

The ongoing study, which has tracked how thousands of Boulder residents get around since 1990, found that bicycle use has nearly doubled since the early '90s while single-occupancy vehicle trips have decreased 7 percent.

The 2009 Mode Shift study, the eighth edition since the city began tracking travel statistics two decades ago, is based on surveys completed by 1,220 random households in Boulder.

Participants were asked to keep a travel diary that shows where they went and how they got there during a random day during the third week of September.

One of the biggest changes over the past 20 years, according to the study, is the number of people who are commuting to work using bicycles or public transportation.

The number of people using vehicles to get to work, and not carpooling, has declined more than 19 percent. At the same time, bus ridership has increased nearly 6 percent and bicycle travel has shot up almost 13 percent.

The study also shows a stark contrast between how far Boulder-area residents travel on average, compared to the rest of the country.

Boulder residents make shorter trips -- an average of 5.1 miles -- compared to the 9.9 miles that an average U.S. resident travels each time they go somewhere.

Boulder residents also spend less time on the roads, at 17 minutes per trip, compared to the 18.7 minutes that an average U.S. traveler spends.

"I think it reflects a lot of things about the community," said Randall Rutsch, a senior transportation planner for the city.

He said the city is relatively compact, with good access to transit options.

"I think we've got a lot of things in place that try and support that trend" of less reliance on vehicles, he said.

The trend toward more buses, bikes and walking, however, is not moving quickly enough to meet Boulder's goals of reducing single-occupancy trips in vehicles.

The overall trend in traffic is not reported in the article, and it was not reported in the most recent report. It can be seen in this presentation from 2008 which shows that in 2007 there was 25% more traffic than in 1994 (slide 15 in this PDF). To meet a goal of 25% reduction in traffic from 1994 levels thus implies a 40% reduction from 2007 traffic. That does not seem presently possible.

The city argues (PDF):

Continued progress in reaching the city’s transportation and climate change objectives will reduce the level of vehicle travel, congestion and air pollution.Emphasizing the distribution of modes of travel rather than the aggregate total won't help reach these goals. Overall, Boulder's transportation policies have had some demonstrable effects (PDF), however, reducing traffic is not among them. In fact, traffic has increased dramatically. This is not the fault of Boulder, of course. But these trends should tell us something about what it will actually take to address increasing accumulations of carbon dioxide emissions.

Ryan Meyer on Malaria in Context

Ryan Meyer, a grad student at Arizona State University, reminds me of an essay that he did for our Center's newsletter in 2006 about climate impacts and malaria in particular. The study in Nature last week on malaria impacts in the context of climate change very much support's Ryan's hypothesis. Here is how Ryan described the issue in his article:

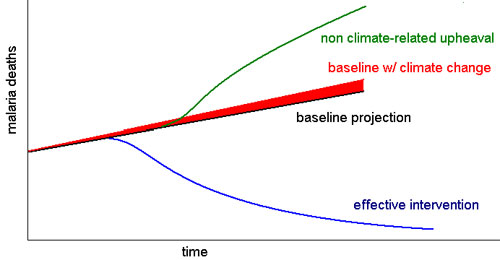

Ryan Meyer, a grad student at Arizona State University, reminds me of an essay that he did for our Center's newsletter in 2006 about climate impacts and malaria in particular. The study in Nature last week on malaria impacts in the context of climate change very much support's Ryan's hypothesis. Here is how Ryan described the issue in his article:Take malaria, for example. Some very simple links have been established that relate climate to the life cycle of mosquitoes and the dynamics of malaria transmission (Rogers and Randolph 2000, Tanser et al. 2003). A quantitative understanding of this relationship can then be used to calculate a marginal change in the number of malaria deaths when the average temperature rises by a given amount – when all other potentially relevant factors remain fixed.Here is how Ryan describes the image above:But of course, we know that all things will not be equal. Many social, political and cultural factors will come into play. Malaria epidemiology may be related in part to climate conditions, but the amount of suffering and death caused by malaria ultimately should have little to do with climate or climate change. For example, the absence of malaria in the southeastern United States, where environmental conditions are conducive to the disease, is due to a massive Centers for Disease Control (CDC) eradication program begun in 1947, which rendered the problem insignificant within four years (CDC 2004). Defeating the disease may be more difficult in some areas than others, but it is nonetheless treatable and controllable through means entirely unrelated to climate change (Sachs 2002).

With that in mind, consider this crude figure showing malaria deaths over time in a hypothetical country where the disease has been a burden historically . . .

The red wedge represents the marginal increase in deaths that a climate impacts model might tell us to expect, all other things being equal. But the baseline projection is actually quite unlikely, especially in the context of an unstable government, a fragile and decaying agro-economic system or, conversely, a transitioning economy with the capacity to eradicate the disease. Whether the problem is largely solved by effective intervention, or greatly exacerbated by non-climate-related disasters like a civil war, overpopulation or some other collapse, the marginal change due to climate is rendered less important. Even if the baseline proves relatively accurate, the impact due to climate change pales in comparison to the massive failure of efforts to intervene in an eminently solvable problem that causes 8 millions deaths a year.If anything, Ryan has over-stated the climate-impacts of malaria as compared to the analysis in the Nature paper which concluded:

. . . the proposed future effects of rising temperatures on endemicity are at least one order of magnitude smaller than changes observed since about 1900 and up to two orders of magnitude smaller than those that can be achieved by the effective scale-up of key control measures.Ryan's essay can be found here.

20 May 2010

Last Word on Malaria?

[UPDATE: In the BBC the lead author of the Nature study has this to say:

[UPDATE: In the BBC the lead author of the Nature study has this to say:"I'd say what we've shown is that if we can provide people with existing technologies such as drugs and bednets, we have the capacity as a global community to reduce the misery this disease causes. Climate change is, in our view, an unwelcome distraction from the main issues."]Yesterday Nature published a paper on malaria and climate change which has concluded (from the abstract):

Our findings have two key and often ignored implications with respect to climate change and malaria. First, widespread claims that rising mean temperatures have already led to increases in worldwide malaria morbidity and mortality are largely at odds with observed decreasing global trends in both its endemicity and geographic extent. Second, the proposed future effects of rising temperatures on endemicity are at least one order of magnitude smaller than changes observed since about 1900 and up to two orders of magnitude smaller than those that can be achieved by the effective scale-up of key control measures. Predictions of an intensification of malaria in a warmer world, based on extrapolated empirical relationships or biological mechanisms, must be set against a context of a century of warming that has seen marked global declines in the disease and a substantial weakening of the global correlation between malaria endemicity and climate.An accompanying Nature News article has this to say:

On the surface, the connection between malaria and climate change is intuitive: higher temperatures are known to boost mosquito populations and the frequency with which they bite. And more mosquito bites mean more malaria.The Nature News article ends on a predictable note, quoting a researcher who says:

Yet when epidemiologists Peter Gething and Simon Hay of the Malaria Atlas Project at the University of Oxford, UK, and their colleagues compiled data on the incidence of malaria in 1900 and 2007 (see page 342), they found the opposite: despite rising temperatures during the twentieth century, malaria has lost ground. According to the models the researchers used to tease out the factors affecting the incidence of malaria, the impact of public-health measures such as improved medications, widespread insecticide use and bed nets have overwhelmed the influence of climate change. "Malaria is still a huge problem," says Gething. "But climate change per se is not something that should be central to the discussion. The risks have been overstated."Some earlier analyses painted a dire picture of a malaria-ridden future, but these models often exclusively evaluated the impact of warmer temperatures without taking other factors into consideration, says Paul Reiter, an entomologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The latest assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change noted these concerns: "Despite the known causal links between climate and malaria transmission dynamics, there is still much uncertainty about the potential impact of climate change on malaria at local and global scales."

"This does not diminish the importance of climate change at all."I agree with this statement of course, because I never thought addressing malaria was a key justification for dealing with climate change in the first place. However the systematic overselling of malaria and climate change in the past requires some attention, and it is not the only context in which these dynamics have occurred -- disasters and climate change provides another obvious example.

Readers from last summer may remember that I took issue with the Global Humanitarian Forum's absurd estimate of more than 300,000 deaths per year due to human-caused climate change, mainly due to diseases and including malaria. The new study underscores my critique.

Hopefully, the new study will mark a new era in the climate debate where it is accepted among the mainstream scientific community to raise challenges to unsupportable claims made to support action, rather than seeing them go unquestioned because of the perceived delicate politics of the climate issue. In this spirit, I see that Andy Revkin, who also discusses the paper, pokes a little fun at one such serial exaggerator.

19 May 2010

Borenstein and Revkin on New NAS Reports

Writing for AP, Seth Borenstein says that the US National Academy of Sciences has embarked o0n a new course of open advocacy and decided to overtly recommend a cap-and-trade program or a carbon tax, which he associates with specific legislation being considered in Congress:

Writing for AP, Seth Borenstein says that the US National Academy of Sciences has embarked o0n a new course of open advocacy and decided to overtly recommend a cap-and-trade program or a carbon tax, which he associates with specific legislation being considered in Congress:In what probably qualifies as the boneheaded comment of the day, the panel co-chair says that it is science that is telling us to act, not anyone's opinions (emphasis added):Ditching its past cautious tone, the nation's top scientists urged the government Wednesday to take drastic action to raise the cost of using coal and oil to slow global warming.

The National Academy of Sciences specifically called for a carbon tax on fossil fuels or a cap-and-trade system for curbing greenhouse gas emissions, calling global warming an urgent threat.

The academy, which advises the government on scientific matters, said the nation needs to cut the pollution that causes global warming by about 57 percent to 83 percent by 2050. That's close to President Barack Obama's goal. . .

In the past, the academy has called climate change a problem, but it has never recommended a specific policy. The impetus for its bolder stance now was a set of questions posed by Congress on climate change and how to deal with it.

The cap-and-trade idea, which is supported by the Obama administration, has been proposed for several years in Congress but never passed the Senate. It would set overall limits on carbon dioxide pollution, but would allow companies to pollute more by paying for it and buying pollution credits from cleaner companies.

Last year, the House approved a cap-and-trade bill, but it stalled in the Senate as health care legislation took center stage. A new version, that doesn't use the cap-and-trade phrase but has similar characteristics, was introduced last week.

"We really need to get started right away. It's not opinion, it's what the science tells you," said academy panel vice chairman Robert Fri, who was acting Environmental Protection Agency chief under President Richard Nixon. "The country needs both a prompt and a sustained commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions."By contrast Andy Revkin sees not much new in terms of advocacy in the report, or in its discussion of policy options:

The Academies, the country’s preeminent scientific advisory body, have issued strings of reports on global warming over the decades. In 1991, the language was already strong and urgent, noting that the risks were sufficient to justify action even with substantial unanswered questions: “Despite the great uncertainties, greenhouse warming is a potential threat sufficient to justify action now.”Revkin also finds no clear linkage with Obama Administration policies or those currently being debated in Congress:

Who has got this right Borenstein or Revkin? Obviously, somebody is spinning madly.The report on “Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change” lays out what would be required to drive an energy revolution in the United States — greatly cutting output of greenhouse gases while sustaining economic well being. It’s a familiar mix of finding ways to add a price to pollution, moving forward with standards and policies that fulfill the huge potential for cutting energy waste and also invigorating the innovation pipeline by greatly boosting investment — public and private — in research and development and the other steps required to generate insights and turn them into new and widely disseminated technologies.

It does not expressly endorse a “cap and trade” approach as opposed to a carbon tax but does recommend creating an overall “budget” for greenhouse gas emissions over a stretch of decades that can lead to a clear, directly measurable goal.

Upcoming Congressional Hearing on Climate Science in the Political Arena

Tomorrow the House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming will hold a hearing on "Climate Science in the Political Arena." The committee has announced the hearing as follows:

Tomorrow the House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming will hold a hearing on "Climate Science in the Political Arena." The committee has announced the hearing as follows:A great irony of this event is that it is set up as a bit of political theater, using scientists as the actors on stage. The hearing witnesses include:The scientists involved in the stolen climate emails from the University of East Anglia were exonerated by the British House of Commons and an international panel of climate experts, led by Lord Oxburgh. Even after these investigations found that nothing in the emails undercut the scientific evidence of climate change, attacks against scientists continue. Reports of harassment, death threats and legal challenges have created a hostile environment, making it challenging for actual data and scientific analyses to reach the public and policymakers.

On Thursday, May 20th, the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming will hold a hearing to examine the intersection between climate science and the political process. This hearing, entitled “Climate Science in the Political Arena,” will feature prominent climate scientists, some of whom have been the target of these attacks. This hearing will explore scientists’ ability to present data and information that can guide global warming solutions in a sometimes fierce political landscape.

Dr. Ralph Cicerone, President of the National Academy of Sciences and Chair of the National Research CouncilUsually, in US Congressional hearing the majority sets the rules for the event, meaning that they get to pick the witnesses and they usually allocate one spot to the minority. In this case it is clear that Happer is the Republican witness, and the others are there at the request of the Democrats.

Dr. Mario Molina, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry and Professor, University of California at San Diego

Dr. Stephen Schneider, Professor, Stanford University

Dr. Ben Santer, Research Scientist, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Dr. William Happer, Professor, Princeton University

Were I a betting type, I'd guess that Schneider and Santer will rail against the deniers, arriving with a laundry list of offenses committed against scientists calling for action on climate change. Happer will say that skeptics have faced the same issues. Everyone will complain, but politics ain't beanbag. You can't swim without getting wet. Cicerone and Molina will have to tread carefully, representing the NAS iand Interacademy Council review of the IPCC, respectively. I'd guess that their testimony will be mainly about procedures and they will be very careful about giving any perception of prejudgment.

Notable is any inclusion on the panel of experts who actually study issues of science and politics. That is because the hearing isn't really about understanding or managing issues of science and politics, but rather, it is an exercise in seeking to gain political advantage through science. It is set up for a food fight, and that is what they will get. Far from shedding light on the politicization of climate science or how to deal with it, this hearing will just add fuel to the fire. That of course is the point. Its about politics, not science.

You can see my own role in the political theater in my testimony on this subject from a hearing held in 2007 here in pdf.

From the Comments

One of the pleasures of blogging is that you get to hear from lots of really smart people. In the comments Harrywr2 had this comment which I thought was worth highlighting.

One of the pleasures of blogging is that you get to hear from lots of really smart people. In the comments Harrywr2 had this comment which I thought was worth highlighting.Country A is going think long and hard before becoming dependent on an energy source provided by country B if they have a long history of animosity.

At the end of WWII France had 3 potential suppliers of coal. The US, UK or Germany.

The shipping costs from the US were prohibitive.

The French added an 'intangible cost' to the market cost of coal. They would rather pay more for their energy then be dependent on the English or Germans.

If I go back to my shopping trips with my wife. My wife and I place a high value on 'marital harmony'. Sears offers us both an enjoyable shopping experience. JC Penney doesn't offer us both an enjoyable shopping experience. Hence, we'll shop at Sears even if the prices are a little lower at JC Penney's

The 'climate debate' for the most part is a debate over what intangible 'environmental costs' should be added to fossil fuel use.

I don't care about drowning polar bears. The cost I'm willing to assign is zero.

I commute to work on a moped. It is my primary means of transportation. I care about not sending money to nasty dictators.

Others may have different intangible costs they assign to the price of fossil fuels.

If I look at Chinese Coal reserves, a substantial portion of it is lignite.

Lignite has a tendency towards spontaneous combustion.

The deeper one goes in a mine the more methane seepage becomes a problem.

Mining lignite in a methane rich environment is pretty close to suicidal. What is a reasonable intangible cost to assign to thousands of coal miners in China being killed in mine accidents every year?

If I look at the various 'Global Decarbonisation' justifications they all use a global average market fossil fuel cost and then add a large(many would say inflated) environmental cost in order to make fossil fuel energy the least desirable energy option.

If I localize fossil fuel costs by assigning shipping costs, add a modest intangible for energy security and a modest intangible for the lives of coal miners I don't need a huge environmental cost to justify decarbonizing the vast majority of the world.

IMHO 'Climate Science' has harmed itself because it falsely believed it needed to justify a huge environmental cost in order to compel decarbonization.

18 May 2010

Pop Quiz

One of the text boxes below is excerpted from comments made today from Todd Stern, chief climate negotiator for the Obama Administration (courtesy Andy Revkin). The other text box comes from a statement made by the Bush Administration 2007. I have edited each to remove references to identifying dates, etc.

One of the text boxes below is excerpted from comments made today from Todd Stern, chief climate negotiator for the Obama Administration (courtesy Andy Revkin). The other text box comes from a statement made by the Bush Administration 2007. I have edited each to remove references to identifying dates, etc.Can you tell which is which (no cheating before considering the question!)? Answers linked below.

Text Box #1

Text Box #2

- . . . it is essential that a new framework include both major developed and developing economies that generate the majority of greenhouse gas emissions and consume the most energy, and that climate change must be addressed in a way that enhances energy security and promotes economic growth. . .

- The U.S. remains committed to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and we expect the new framework to complement ongoing UN activity.

- The President’s proposal breaks new ground in advancing areas of common interest between developed countries and the major emerging economies. . .

- The proposal seeks to bring together the world’s top greenhouse gas emitters and energy consumers.

- In creating a new framework, the major emitters will work together to develop a long-term global goal to reduce greenhouse gasses.

- Each country will work to achieve this emissions goal by establishing its own ambitious mid-term national targets and programs, based on national circumstances.

- They will ensure advancement towards the global goal with a review process that assesses each country’s performances. . .

- America is leading the way with clean energy technology and is stepping up efforts to make advanced energy technology commercially viable. . .

- We have now reached a pivotal moment where advances in technology are creating new ways to improve energy security, strengthen national security, and protect the environment.

When you are ready here are the sources for Text Box #1 and Text Box #2.

- . . . we can only understand the challenge of moving to a new paradigm if we start by focusing on what came to be accepted by many – although not all and not us – as the old paradigm.

- That paradigm held that the world is sharply divided into two camps that never overlap and never evolve – developed countries and developing countries, as they were defined in 1992 in the Framework Convention, with all real obligations to address climate change accruing to developed countries. The Kyoto Protocol has often been read to enshrine this division. . .

- Now, there are multiple problems with this paradigm. First, it is wrong as a matter of textual exegesis. In addition, it is fatally flawed substantively and politically as a foundation for the future. . .

- Most fundamentally, you cannot address the climate challenge by focusing only on developed countries; they account for around 45% of global emissions now and will account for some 35% by 2030. Instead, you need to start with the 85% of emissions represented by the major economies and build out from there. Moreover, as a matter of political reality, we could get no support in the United States for a climate agreement that required action of us but not from China and the other emerging markets. . .

- [The new paradigm] reflects a bottom-up architecture, first proposed by Australia, based on countries committing to measures rooted in their own domestic programs. We would argue that this is the only practical way forward if you mean to include all significant economies, because no across-the-board, top-down target would be acceptable at this stage to developing countries or, indeed, to us. . .

- In our view, such an agreement would include domestically derived mitigation commitments for all the major economies and as many others as possible. It would include robust transparency provisions for all countries, both so that we are all able to keep track of how we are doing in reducing emissions globally and so that all countries can have confidence in the mitigation commitments made by others.

- And it would include far-reaching provisions on funding, so that developing countries, particularly the needier among them, are given the kind of support they need for both mitigation and adaptation.

- Such support needs to include assistance in acquiring and using technology as well as in the means to avoid deforestation.

The Hartwell Paper is Available in Chinese

For readers in China, The Hartwell Paper is available in Chinese at this link (PDF).

For readers in China, The Hartwell Paper is available in Chinese at this link (PDF).Please share far and wide. Thanks!

China's Proposed Carbon Tax

Michael Levi has a nice overview of the carbon tax proposal of the Chinese government. He writes:

Michael Levi has a nice overview of the carbon tax proposal of the Chinese government. He writes:Barbara Finamore at NRDC has a nice rundown of internal Chinese discussions about imposing a carbon tax beginning in 2012. A Chinese carbon tax would be a positive development. But it’s important for observers to understand what it would do and what it wouldn’t. Based on the numbers being discussed, this looks like it’s more about raising money (albeit money that might be earmarked for green “research and development investment”) than about directly altering Chinese emissions: the tax being proposed would be equivalent to about $1.50 per ton of CO2 in 2012 and would rise to a bit less than six bucks by 2020. . .Levi suggests some irony in how the proposed tax is being received:

The report that Barbara cites envisions a tax of 10 RMB per ton of carbon dioxide starting in 2012, rising to 40 RMB in 2020. Coal generates (PDF) about a kilogram of emissions for every kilowatt-hour of electricity produced. The hypothetical Chinese carbon tax would thus raise prices of coal-fired electricity by about 0.01 RMB/kWh in 2012 and 0.04 RMB/kWh in 2020. Put that in context: electricity prices (costs are obviously somewhat lower) in China range from about 0.5 to 0.8 RMB/kWh.Here’s another way to look at it. A recent OECD study projects a 3 c/kWh cost for coal generation in China, a 3.6 c/kWh cost for gas, and a 3-3.6 c/kWh cost for nuclear, the cheapest non-emitting option (all assuming a 5% discount rate). A 0.01-0.05 RMB/kWh carbon tax adds 0.0015-0.006 c/kWh to the cost of coal generation, which simply does not change decisionmaking. (If one uses a 10% discount rate, coal comes in at 3.3 c/kWh, nuclear at 4.4-5.5, and gas at 3.9, making the gap even bigger.)

Praise from the environmental advocacy community for this step is thus more than a bit ironic: it’s pretty much in line with what The Breakthrough Institute, Roger Pielke Jr, and Bjorn Lomborg have called for.As Rasheed Wallace once said in a philosophical moment, ball don't lie ;-)

The Definitive Denier

The tyranny of denial

“Denial” is an ordinary English word meaning to assert the untruth of something. Recently, however, it has acquired a further polemical sense. To “deny” in this new sense is to repudiate some commonly professed doctrine. Denial is the secular form of blasphemy; deniers are scorned, ridiculed and sometimes prosecuted.

Where does this new usage come from? There is an old sense of “deny,” akin to “disown,” which no doubt lies in the background. (A traitor denies his country; Peter denied Christ.) But the more immediate source is Freud. Denial in the Freudian sense is the refusal to accept a painful or humiliating truth. Sufferers are said to be in a “state of denial” or simply “in denial.” This last phrase entered general use in the early 1990s and launched “denial” on its modern career. “Holocaust denial” was the first political application, followed closely by “Aids denial,” “global warming denial” and a host of others. An abstract noun, “denialism,” has recently been coined. It is perhaps no accident that denial’s counterpart, affirmation, has meanwhile acquired laudatory overtones. We “affirm” relationships, achievements, values. Ours is a relentlessly positive culture.

An accusation of “denial” is serious, suggesting either deliberate dishonesty or self-deception. The thing being denied is, by implication, so obviously true that the denier must be driven by perversity, malice or wilful blindness. Few issues warrant such confidence. The Holocaust is perhaps one, though even here there is room for debate over the manner of its execution and the number of its victims. A charge of denial short-circuits this debate by stigmatising as dishonest any deviation from a preordained conclusion. It is a form of the argument ad hominem: the aim is not so much to refute your opponent as to discredit his motives. The extension of the “denier” tag to group after group is a development that should alarm all liberal-minded people. One of the great achievements of the Enlightenment—the liberation of historical and scientific enquiry from dogma—is quietly being reversed.

Steve McIntyre on Hot Fudge

It looks like Steve McIntyre and I share similar views in the fudge vs. fraud debate:

It looks like Steve McIntyre and I share similar views in the fudge vs. fraud debate:The person who was most instrumental in debunking Climategate scientist Michael Mann's hockey stick chart, Steve McIntyre of Climate Audit, said last night that he did not believe his scientific misrepresentations rose to the level of fraud. . . McIntyre said he believed expressing emotions and anger over the episode was counterproductive and even self-indulgent, and that simply proving Mann and others wrong was sufficient.McIntyre also spoke out against the Virgina Attorney general's fishing expedition:

“Regardless of what one may think of the quality of Mann’s work,” McIntyre said, “he has published diligently. ... [The Virginia AG’s actions] are an abuse of administrative prerogative that ... is unfair to Mann.”

17 May 2010

He's Baaack

Joe Romm is back on the attack. After he turned down a debate with me that would have raised $20,000 for Doctors Without Borders, he was quiet for a while. But it didn't last long.

Joe Romm is back on the attack. After he turned down a debate with me that would have raised $20,000 for Doctors Without Borders, he was quiet for a while. But it didn't last long.What has Romm's knickers in a twist this time?

Apparently it is the following quote of mine which appeared in an interesting Boston Globe article profiling the many-decades relationship of Kerry Emanuel and Richard Lindzen.

“If these two guys can’t agree on the basic conclusions of the social significance of [climate change science], how can we expect 6.5 billion people to?’’ said Roger Pielke Jr., a University of Colorado at Boulder professor who writes a climate blog.The point here should be obvious -- not everyone will come to agreement on the social significance of climate science, and it is not simply because they have different views on the science, as the Globe article well explains. Action on climate change will have to be based upon a broad agenda of common interests beyond carbon and climate, a key point of our recently issued Hartwell Paper. Agreement on climate science or what it signifies is unnecessary for action to occur.

In classic Romm fashion he starts with an outright lie -- "Lindzen apparently doesn’t want any meaningful action at all — much like Pielke." He then decides apparently that because agrees with me, he needs to pretend that I said the opposite of what I said, so he can then impeach that view that I don't hold. Twisted, I know.

He writes (emphasis in original):

Right, Joe. This is exactly my point. I'm glad you agree. But really, is this the best you can do? No wonder you declined to debate!Since when do we have to wait until 6.5 billion people agree before we act on a global problem of massive social significance? Somehow we managed to eradicate small pox without the entire planet adjudicating the risks.

More to the point, we managed to save the ozone layer without the entire planet agreeing on the basic conclusions of the social significance of [ozone science]. And yes, the climate change problem is a quantum leap difference in scale and difficulty than the ozone problem.

I fear that Romm is going to explode when The Climate Fix comes out. It won't be a pretty sight.

Five Myths

[UPDATE: Keith Kloor has an interesting take on this debate, and helpfully reminds me that I've made these points before. Also, I've modified this post with the material in brackets below, thanks to a helpful comment from a reader.]

[UPDATE: Keith Kloor has an interesting take on this debate, and helpfully reminds me that I've made these points before. Also, I've modified this post with the material in brackets below, thanks to a helpful comment from a reader.]The comments that I've received and exchanges that I've had with a fair number of people over the past few days about issues of scientific fraud as related to the so-called hockey stick indicate a few things. First, some people are really, really angry. And I mean red-in0the-face livid such that they aren't going to hear anything except their own indignation. These folks won't be convinced of anything. There are others whose views are fueled by myths -- views that are not just wrong, but unhelpful in trying to make sense of the issue. Still others simply have a different take on issues than I do.

This post is focused on the second of those three categories -- those who repeat common myths in the discussion. Here are a few of those myths:

1) Myth: Science provides absolute truths and scientific misconduct can be identified as any action that moves science away from truth.Reality: Science is messy. Claims can be argued many different ways. [Successfully adjudicated cases of] scientific misconduct are very rare and exceedingly hard to prove. Since truth is determined via scientific debates, using it as a fulcrum on which to adjudicate misconduct is obviously problematic. Hard cases, as they say, make bad law. The same goes here as well.

2) Myth: Policy makers care about tree rings, temperatures of the Middle Ages or other arcane details of climate science.Reality: They don't. It is easy to confuse politics and policy. Almost all debates about climate science are purely political, with little or even no policy connection. In any case, effective climate and energy policies will be robust to scientific uncertainties and associated politicized debates.

3) Myth: Billion or even trillion dollar decisions are being made based on the Hockey Stick, or more expansively, the claims of IPCC WG I.Reality: No such decisions hinge upon the correctness of the Hockey Stick. None. It is a political symbol. The IPCC WG I has established that there is an issue of risk management that might occupy your attention. It is in fact a pretty low threshold to reach. IPCC WG I says nothing about what our options are or what we should do.

4) Myth: There are mechanisms for identifying and correcting mistakes, misrepresentations and, yes, fraud, under the IPCC.Reality: These terms aren't even defined under the IPCC much less set forth in guidelines for practice. All of the anger in the world isn't going to change this fact. Discussing institutional reform might, for some, be a bit like getting a root canal, but it is where improvements in institutions (and thus practices) of climate science will come from.

5) Myth: Getting very angry, calling me names and being rude will make me see the wisdom in your views.Reality. No, it won't. Please keep the discussions respectful. In the end, it is OK for people to agree to disagree.